New Woman Fiction Needs the Inevitable: An Essay on “Ellen” by Mrs. Rudolf Dircks

Introduction

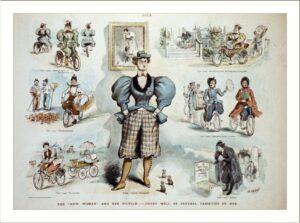

Representations and definitions of ‘feminism’ have changed drastically over the last few centuries. It is the angering and complicated history of feminism that has allowed this change to occur; this leads academics to ponder the ways in which feminism is historically discussed and represented in art, culture, and literature. In the 1890s, female authors began using the power of literature and language to construct narratives that fit into their emerging feminist ideas. Thus, The New Woman was born. Both a character and genre, the New Woman demanded action, autonomy, and female emancipation. She was beloved, she was hated, she was what women desired to be.

The Savoy, an influential periodical that ran in 1896, under-represents the New Woman entity perhaps in order to adhere to its strict and self-insinuated anti-Decadent agenda. Many prominent and influential New Woman texts of the time were classified as Decadent, making Aestheticist New Woman narratives scarce. Despite this, The Savoy manages to include an interestingly feminist, and evidently New Woman, piece entitled “Ellen” in their first issue. Written by Mrs. Rudolf Dircks, this short story uncovers the relationship between female emancipation and female psychology, by demonstrating the various psychological impacts of patriarchal societal norms. In this essay, I argue that “Ellen” both works as a contribution to and a criticism of prominent New Woman fiction from the 1890s. By following Ellen’s character development throughout the story, I will analyze the text’s New Woman and psychological elements and, through their interconnectedness, I propose the emergence of “the Inevitable New Woman”. It is through accepting this Inevitable New Woman that the New Woman genre can diversify and change forever.

Who is the New Woman and Why is she Important?

The New Woman figure and genre has been studied by many academics who are interested in the literary beginnings of feminism. In the 19th Century, culturally informed authors and academics aspired to a deeper interpretation of the feminist protagonist. They aimed to challenge stereotypes and construct complex ideas about feminism.

Lyn Pykett describes this character best as “…a construct, ‘a condensed symbol of disorder and rebellion’ who was actively produced and reproduced in the pages of the newspaper and periodical press as well as in novels” (137-138). The New Woman was everywhere, written through every literary medium that served her main purpose: to demonstrate “‘The spectacle of femininity in crisis’” (Pykett 142). She pursued liberation through various means, though, the most popular being through an embrace of sexual desire, sexuality, bodily autonomy, and more. The genre also drew on scientific discourse of the time to introduce psychological side effects of patriarchal systems and expectations, something we see in “Ellen”.

The New Woman genre met its challengers at the height of its success, with critics suggesting that The New Woman “was a creature whose proper feminine affectivity…had become excessive and degenerate and had thus entered the domain of the improper feminine” (140). In other words, critics believed that The New Woman’s feelings of inferiority were a result of the female sex’s emotional tendencies rather than oppression, thus leading them to be classified as “the improper feminine”. Nonetheless, female – and male – New Woman authors sought female liberation with determination, by using literature and language to “[push] against and [disturb]…boundaries” (142). In “Ellen”, it is clear that Dircks uses these New Woman origins and perceptions to her advantage in order to portray Ellen as a feminist, New Woman character.

Introducing “Ellen”

“Ellen” is a story about self-awareness, growth, and self-expression. Set in London in the 1890s, Ellen is surrounded by the members of a bustling and growing city. In many ways, the story, its placement within The Savoy, and historical context make it adjacent to New Woman fiction. This allows Dircks to portray a more realistic example of what female emancipation looks like through Ellen’s natural character development.

Exposition

In the exposition of “Ellen” we meet our protagonist, our New Woman, Ellen as she works at a cafe in the city. At the moment we meet her, Ellen’s life is stagnant. The narrator mentions, “..her circumstances had not changed during that time ; she herself had scarcely changed ; her features had, perhaps, developed a little and become more defined, her manner less hesitating—and that was all” (Dircks 103). Our introduction to Ellen is pitiful, as it is evident her life is unrewarding.

Dircks uses the exposition of her story to introduce Ellen’s main psychological conflicts. It is revealed that Ellen longs for a companion but is unwilling to do what is expected of her to reach this goal. Ellen “regretted her want of adaptability, of the faculty of being able to assume all those charming (as they seemed to her) little airs and graces, partly natural, partly cultivated, which so became the other girls ; she, it is true, rather despised these coquetries of her companions, but her own deficiencies of the sort made her feel at times particularly dull and stupid and angry with herself” (103). Evidently, Ellen is not willing to be flirtatious to appeal to men and, yet, regrets and becomes angered with that same unwillingness as it feeds her loneliness.

Furthermore, readers are immediately plunged into a feminist space as the story discusses love, companionship, men, and women, which were often found in New Woman narratives (Pykett 143). Pykett writes that “…women’s lives [in New Woman narratives] are presented as inherently problematic, and unhappiness is the norm. Whatever path they choose, whether they conform to or break with convention, women are likely to be thwarted and frustrated” (148). We can see this in the beginning of “Ellen”, as her independent and empowered mindset recognizes how diminishing it would be to play into male fantasies, while her assimilating mindset struggles to diverge from social norms. Ultimately, the exposition demonstrates where Ellen is at the beginning of her emancipation journey, though the latter half of the story witnesses her change.

Rising Action

In the rising action of “Ellen”, readers witness the greater heights of the story’s feminist lens as well as Ellen’s psychological distress. Discussions of men, women, and marriage are further explored in the rising action. Readers learn that Ellen views men as “silly” and “wicked” and declares that women possess “trivial insecurities” (104). She overly observes the men and women around her to the point in which they seem unappealing. With these perceptions of men locked in her mind, she does not believe “that she would ever fall in love, [or] that anyone would ever fall in love with her” (104).

Not only does she make these observations of those around her, but she brings these observations inward to discover and make perceptions about her own being and life. Ellen “had an intuitive suspicion that she possessed qualities which would be fatal to her retaining the affections of a husband, that there would be little joy for her in the companionship which would place her in the position of a wife” (104). Once again, discussions of love and marriage position this as a worthy New Woman text. Not simply because they are mentioned, but because these thoughts plague Ellen’s mind and demonstrate the complexity of femininity and “‘the spectacle of femininity in crisis’” (Pykett 142). Pykett further explains that New Woman authors “focused minutely on the domestic space and…engaged in a probing exploration and critique of marriage and the family” (143). What is ‘probing’ about Dircks’s story is its ability to define the difference between merely including New Woman topics like marriage, family, etc. and the act of diving deeper into these topics’ effect on women. This is where the psychological aspect of “Ellen” becomes important.

Readers recognize symptoms of dissociation/daydreaming, depression, loneliness, and childhood trauma within Ellen at this time. Ellen’s dissociation is apparent: “…the vague emotions and sensations which moved her, the detached things which floated in her mind had not yet found the relief which comes with realisation; her impulses were not remotely guided by self-consciousness” (104). Undoubtedly, Ellen is experiencing an out-of-body sensation that removes her from her consciousness. In fact, depictions of dissociation and daydreaming were common in New Woman narratives. Daydreaming was “a metaphor for female resistance” and “provided women with an outlet for their repressed desire” (Heilmann 131). What this suggests is that Dircks included Ellen’s dissociation and daydreaming tendencies to contribute to the female liberation discussions. Ellen’s ability to remove herself from the present moment is both a side effect of her intense internal conflict, as well as a way for her to resist social norms and act on her authentic impulses.

As well as dissociation and daydreaming, Ellen’s alienation is emphasized. Readers learn that Ellen possesses “[a] sense of loneliness [that] oppressed her…” and “this sense of loneliness [appeared] even in the busiest time of the day, when an enormous wave of traffic swept by outside the café, and, inside, all was stir and movement” (Dircks 104, 105). It is even revealed that she was orphaned as a child, leaving Ellen alone and without love and care. What Dircks does here is provide an explicit reason for this psychological distress that Ellen feels. A lot of New Woman writers would draw “on contemporary medical discourse in order to undermine patriarchal authority by exposing its destructive impact on female identity”, despite many psychological discourses excluding women from their studies (Heilmann 123). In fact, many male psychologists failed to provide unbiased studies of women for women and “misogynistic bias prevented male scientists from seeing women’s individuality beyond their sex” (Leng 48). Like many New Woman authors of the time, Dircks comments on this “scientific misogyny” by including realistic examples of the ways in which women experience loneliness and other psychological issues as a result of traumatic or triggering experiences (47).

This pscyho-feminist discourse therefore provides Dircks the opportunity to create a more believable and representative portrayal of female psychology, as she demonstrates the influence of patriarchal social norms on the psyche and how this contributes to a nuanced New Woman discussion.

Perhaps the most pivotal moment in the story occurs when Ellen meets a man from the cafe who sparks her interest almost immediately. After analysis, it is clear that The Man is an embodiment of psycho-feminist discourse, as he becomes a vehicle that Ellen uses to achieve liberation and full consciousness, meaning she achieves her status as the “Inevitable” New Woman. Ann Heilmann writes that “the transition from internalized conflict to externalized anger” lost “its liberating potential…unless this externalization did in fact take place” (123). The Man provides the space for Ellen to externalize her psyche.

Even Ellen herself realizes the opportunity before her, as The Man’s “presence accentuated a dimly-realised need for self-expression, of pouring into some ear the flood of vague sentiments which possessed her” (Dircks 105). Many male scientists attributed women’s mental illness and affectability to their lack of “‘outlets of action’ through which their sexual feelings and energies ‘might be discharged vicariously” (Hetherington 156). Ellen does not experience this sexual repression, however, Dircks positions psychological expression as equally necessary as sexual expression. Therefore, The Man remains an “‘outlet of action’” with which Ellen purges her mind and body of her distress. By the end of “Ellen”, readers notice a dramatic shift in Ellen’s character, as this male figure finds his purpose in the story.

Denouement

In the story’s ending, the titular character reaches her full potential. On their outing, Ellen denies The Man’s physical advances and “[a]fter this, his manner changes, and she felt more at ease” (Dircks 107). Resultantly, this gave her the opportunity to relax, as there were no expectations of her. Suddenly, “…all the things that had lain in her mind, all the incoherent emotions that had possessed her, became coherent and simple, derived shape and form in the attempt to express them” and “[s]he told him of the feeling of loneliness, of abstraction, of the vague itching at her heart which never ceased” (107). Here, psychological expression is evident, as these plaguing feelings of alienation and unworthiness become verbalized and transmitted to The Man. This is how Dircks derives a psycho-feminist lens within the story, as she uses psychological ideas, “claim[s] an authoritative, objective voice [and] reconcile[s] it with a feminist standpoint” (Leng 55).

This is further emphasized through “Ellen’s” most pivotal moment when Ellen inherits full bodily and female autonomy through an expression of choice. The Man’s presence and role as an “‘outlet of action’” finally allows Ellen to understand what she truly desires in the realm of marriage and motherhood, two common themes in New Woman literature. Ellen reveals, “‘I don’t want to be married, the same as most girls do; I don’t like men, as a rule–at least, not in that way…besides, I think I should always be happier remaining as I am at the present, working for myself, independent’” (Dircks 107). Many women in the 19th Century experienced conflict with one another over the credibility and necessity of marriage. Lyn Pykett writes that “[a]t one extreme marriage was seen (by both feminists and anti-feminists) as woman’s highest and most natural calling. At the other it was a form of slavery or legalised prostitution” (144). Clearly, Ellen fits into neither extreme, however, she does contribute to a broader New Woman discussion by saying she merely does not want to get married. In the process, she refrains from critiquing marriage in totality and does not critique those who choose to participate in it. Instead, Ellen merely states what her personal choice is, that is, that she chooses to remain unmarried and independent. Once again, The Man’s presence evidently provides Ellen the space to achieve full autonomy of her mind.

Ellen’s moment of bodily autonomy comes at the very end of the story, when she tearfully discusses motherhood. She says, “‘I think…if I had a baby, my very own, I should want nothing—nothing in this world more than that!’” (Dircks 108). This is the last moment in which “Ellen” critiques prominent New Woman work and ideals. Despite her choice to remain unmarried, Ellen still wants to experience motherhood. This contributes to a larger New Woman discussion. “Ellen” embodies “[t]he general effect of the New Woman novel [which] is to suggest the ‘impossibility of women’s situation,’” while also challenging New Woman notions by refraining to critique motherhood and those who do or do not participate in it (Pykett 148). By integrating Ellen’s personal choice, Dircks creates a unique representation of New Women that demonstrates a heightened analysis of what feminism stands for, and the future it provides women – which is full body and mind autonomy.

The Inevitable New Woman

From the analysis above, I have depicted the character development that Ellen progresses through in this text. Undoubtedly, Ellen in the exposition fails to connect with her body and mind’s needs and is ignorant to her internal conflict. By the end of the story, Ellen is given the space to consider and verbalize her deepest emotions and express her psychological distress, leading her to full consciousness and physical liberation.

This transition is critical to the creation of the Inevitable New Woman. Using “Ellen” as my only example, my definition of the Inevitable New Woman is: A female protagonist from the late 19th Century who demonstrates common New Woman traits, feelings, and mindsets in a nuanced way, demonstrating how female emancipation is likely to occur through natural character development. In short, The Inevitable New Woman is a figure whose liberation is bound to occur as a result of the combination between the weight of patriarchal values and human nature.

What “Ellen” specifically demonstrates is that New Woman stories can be simple and veer from their traditional identifiers such as themes of sexuality and hysteria. These intense events that lead to women’s emancipation are arguably exaggerated. In “Ellen” themes like motherhood, marriage, and independence, which, as discussed, were themes many New Woman authors addressed, are much more muted and based around the idea of women’s choice rather than women’s rejection of patriarchal values.

One might argue that the New Woman genre is fixed and, after being studied for many years, does not require any more distinctive categories within it; however, I argue that The New Woman cannot be defined by a single definition, story, or character. Sally Ledger emphasizes this when she writes that, “The ‘wild woman’, the ‘glorified spinster’, the ‘advanced woman’, the ‘odd woman’;…all these discursive constructs variously approximated to the nascent ‘New Woman’” (3). What can be inferred from this is that the New Woman genre and character was formed by complex predecessors that depicted emerging attributes and mindsets of early feminists and feminism. The Inevitable Woman, then, has the potential to nestle within the world of New Women.

By integrating scientific consequences of patriarchy, Dircks brings in another element to Ellen’s “inevitable” emancipation. Ellen’s natural character development does not occur as a result of exterior events but, rather, as a result of interior events. Only through verbalizing her interior and suppressed thoughts does Ellen become fully liberated. This argues that New Woman emancipation does not have to occur solely through physical expression but through psychological expression as well. In short, “[s]cience offered to establish empowering ‘laws’ about sex and sexuality, and to present women’s emancipation as the inevitable unfolding of natural processes” (emphasis added, Leng 40). Ultimately, “Ellen” concludes that New Woman literature has the potential to be simplistic and still convey its feminist ideas.

Furthermore, this Inevitable New Woman represents a broader group of women which could help contribute to the diversification of the New Woman genre. Arguably, the New Woman genre and scholars within it have failed to accurately represent New Woman authors in the 19th Century by studying authors that resided in western countries and had access to the west’s cultural and artistic resources. Ledger recognizes this as well: “[t]extual representations of the New Woman…did not always coincide at all exactly with contemporary feminist beliefs and activities…A good deal of material, and great number of writers have necessarily been excluded” (1). What “Ellen” and Mrs. Rudolf Dircks project is the eventual and necessary diversification of the New Woman genre through its depiction of the Inevitable New Woman.

Conclusion

Contemporary society revels in the progression feminism has made throughout these last centuries. It is important, however, to uncover deeper parts of feminist history in order to understand the future of the movement. Uncovering The New Woman genre and its narratives was an incredible step in the right direction, however, there is always room to expand on the meaning and legacy of this genre. What The Inevitable New Woman suggests is that emancipation does not have to be forced to feel liberating. Dircks uncovers many complexities within feminism that I believe can de-segregate the New Woman genre and force New Woman scholars to study works outside their traditional beliefs. As academics, we have a duty to provide research that benefits contemporary movements and challenges our current understandings of the world. We do it to make the world easier to live in for students, scholars, and all members of society.

Works Cited

Dircks, Rudolf. “Ellen.” The Savoy, Jan. 1896, pp. 103-108.

Heilmann, Ann. “Narrating the Hysteric: Fin-de-Siècle Medical Discourse and Sarah Grand’s: The Heavenly Twins (1893).” The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact: Fin-de-Siècle Feminisms, edited by Angelique Richardson and Chris Willis, Palgrace Publishers, 2001, pp. 123-135.

Hetherington, Naomi. “The Seventh Wave of Humanity: Hysteria and Moral Evolution in Sarah Grand’s The Heavenly Twins.” Writing Women of the Fin de Siècle, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011, pp. 153-165.

Ledger, Sally. “Introduction.” The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin-de-Siècle, Manchester University Press, 1997, pp. 1-8.

Leng, Kristen. “Sex, Science, and Fin-De-Siècle Feminism.” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 25, no. 3, 2013, pp. 38-61.

Pykett, Lyn. “The New Woman.” The ‘Improper’ Feminine: The Women’s Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing, Taylor and Francis Group, 1992, pp. 137-142.

Pykett, Lyn. “The New Woman writing and some marriage questions.” The ‘Improper’ Feminine: The Women’s Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing, Taylor and Francis Group, 1992, pp. 143-153.

Pykett, Lyn. “Woman’s ‘affectability’ and the literature of hysteria.” The ‘Improper’ Feminine: The Women’s Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing, Taylor and Francis Group, 1992, pp. 164-176.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair

dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of

research, private study, or education.