Feminist Perspective of Artwork and John Masefield’s Poems in The Venture

© Copyright 2022 Sydney Dowling, Toronto Metropolitan University

John Masefield

John Masefield was a relatively well-known poet during the fin de siècle. Born on June 1st, 1878, Masefield spent his life perusing other ambitions rather than just writing. Being an apprentice on a commercial sailing ship, working at a carpet manufacturer in The United States, and then settling down as a journalist in London; his acquired knowledge of the world is directly apparent in his poetry. Additionally, his poems are commonly characterized as melancholy and informal, which was rather unusual at the time. Although his publications in The Venture were not amongst his most well-established work, and do not have preceding research, they serve as a purpose to illustrate the feminist perspective, and how society perceived women during the fin de siècle.

“When Bony Death Has Chilled Her Gentle Blood”

Masefield’s First poem in The Venture

John Masefield’s “When Bony Death Has Chilled Her Gentle Blood” is the first piece of literature exhibited in volume one of The Venture. Demonstrating the overall aesthetic of the magazine as well as illustrates Masefield’s austere writing style, the poem conveys the story of a women who has died and the events that follow. The poem then describes how men react to her passing, showing their continued concern for appearances even after death. As the men reminisce on her beauties, the narrator, through the use of beautiful imagery, expresses the grief he feels after her passing. The poem ultimately depicts the two perspectives men had on women: one, a simple concern with a woman’s external beauty despite the tragic loss that had occurred, and two, the grief following the loss of someone close and remembering how profoundly they touched you, as well as the challenges of moving on.

The fin de siècle was a time period that focused on modernism. This turn-of-the-century granted women the hope to abolish the hardships they were enduring in the past. Prior, The Victorian Era did not grant women many rights. Particularly “they were viewed as only supposed to be housewives and mothers to their children” (Barret, 2013). However, the fin de siècle introduced a new image of women, ‘The New Women’ who was more complex, sexual, and independent. It’s crucial to illustrate how women were viewed in the past to ensure that the same error is not repeated since gender was and is a complicated term that is continually changing and being expanded upon. Sally Ledger explores the conflicting views people had on women, particularly in fictional works such short stories, poetry, and drama, in her 1997 novel The New Women: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle. “Gender was an unstable category at the fin de siècle,” in fact the ideas of the importance of women and femininity was a new concept being explored by writers everywhere (Ledger, 2). However, many authors (primarily men) went against the ‘New Women’ ideology and turned the phenomenon into a controversy.

The way women were perceived at the fin de siècle can be depicted through the poetry John Masefield wrote for The Venture and illustrates how he contrasts the two sides of the literary ‘New Women’ movement. First, death is characterized as a man demonstrated through how he uses “his old skill in hateful wizardries.” Initially through his melancholy writing, Masefield chooses a destructive and powerful symbol to give to men (Masefield, 1). On the other hand, he portrays women as innocent and gentle, and the victim of death seen through the description that death “dimmed the brightness of her wistful eyes and stamped her glorious beauty into mud (Masefield, 1). Through the inevitability of death, characterizing it as man detrimentally demonstrates the stereotype that women will not be equal to men and will remain to be passive and submissive to them. Through Justin Prystash’s exploration into feminism at the fin de siècle he concluded that many pieces of literature published at this time sexualized women in a negative way and “reveal[s] the potential for fin-de-siècle speculative fiction to alter sex beyond the recognizable (Prystash, 344). This concept can be illustrated through the men’s descriptions of the woman who passed away. “How red a lip was hers… when rheumy gray-beards say, ‘I knew her well,’ showing the grave to curious worshippers” illustrates how a woman’s legacy is overshadowed by how men view her, even after she has passed away (Masefield, 1). The lines “leaving no greenery on any tree that her dear hands in my heart’s garden laid” demonstrates how significant the woman was in the narrator’s life and how much sorrow they are experiencing, emphasizing that the narrator isn’t only concerned with appearances (Masefield, 1).

“Blindess”

Masefield’s Second Poem in The Venture

John Masefield’s second poem published in The Venture entitled “Blindness,” shares an additional viewpoint on women during the fin de siècle. “Feminism [at the fin de siècle] was both a product of social relations and itself an agent in their transformation;” women in different social classes were beginning to understand the power dynamic between men and women and understood that there needed to be change (Young Lim, 5). In addition, this time period was a crucial time for the progression of women’s rights and “during the course of the nineteenth century women had increasingly challenged their subordinate social and political position” (Richardson and Willis, 1).

As authors were mostly men at the fin de siècle, it created a challenge for women to promote new conventional ideas on their gender. In contrast, Masefield departs from the ‘New Women’ perspective in the poem “Blindness” and instead portrays women in a ‘traditional’ manner to highlight the superiority males believe they had over women. The poem begins by assigning the sentiment of love to a feminine character. The first wave of introducing the ‘New Women’ movement attempted to articulate the concept that “men and women were made up of both masculine and feminine qualities” and literature should not assign certain characteristics scarcely because of gender (Macpherson and Pearce, 42). However, contrasting to how he compares death to a man in “When Bony Death Has Chilled Her Gentle Blood,” which promotes the notion that men are as powerful as death which is permanent and something everyone fears; he uses an emotion that is tender, compassionate, and gentle for women which evidently demonstrates that this notion was not in consideration.

Furthermore, Masefield particularly emphasizes women’s attractiveness in the poem, which demonstrates irony given the title “Blindness.” Through the lines, “And borne her sacred image richly set,” “the dear friend whose beauty I extol,” and “I have learned how rare a women shows as much in all she does as in her looks” are mere examples of the narrator only focusing on the appearance of the women he is describing (Masefield, 74). Only years before the publication of volume one of The Venture, a group of women in London argued that clothes men typically viewed as “feminine” including “tight corsets, high heels, and unwieldy skirts- was absurd;” which supports the notion that women were appalled by men’s persistent attention on beauty (Macpherson and Pearce, 42). Additionally, the poem concludes with the narrator reflecting on himself and realizing that his attention to the woman’s beauty had blinded him from other, more crucial characteristics. He says, “All I have learned, and can learn, shows me this- How scant, how slight, my knowledge of her is” (Masefield, 74). The opportunity to get to know the woman was lost because the narrator was so preoccupied with her physical beauty; instead, he was left with the realization of his mistake. It’s critical to comprehend the attention and emphasis placed at the fin de siècle on the “subversive nature of [being] feminine,” given that “women are ideologically constructed through language” (Gavin, 1).

It is evident that the two poems by John Masefield in The Venture oppose one another while simultaneously illuminate the various perspectives on women held by society at the fin de siècle. In fact, “viewed as frivolous and incapable of rational thought, a women was expected to beautify herself and her home, as well as attend to her husband and children.” (Roberts, 3). Women were considered to be objects, only capable of being mothers, enhancing their appearance, and tending to men. At the turn of the century, most people did not share the belief that women could be more than simply their outward appearance. This is particularly clear when Masefield’s poetry is analyzed from a feministic standpoint. In “When Bony Death Has Chilled her Gentle Blood,” the narrator places more emphasis on how the woman impacted him than on how she looked. This idea was not widely accepted or embraced by the general public, which illustrates the unpopular trend towards the ‘New Women’ movement. However, the poem “Blindness” contradicts this notion by showing the narrator as being seduced by the woman’s attractiveness but failing to give in to her other traits. Furthermore, a crisis of sex roles centred on the system of beliefs and practices that tried to govern the concepts of male and female also began to manifest towards the end of the nineteenth century when women came under more scrutiny (Roberts, 3). Lastly, the two poems successfully convey the prejudiced viewpoints that the society at the turn of the century held. Women campaigned for increased and realistic representation in literature, and also broader political rights as they challenged the gender hegemony and their domestic responsibilities as housewives.

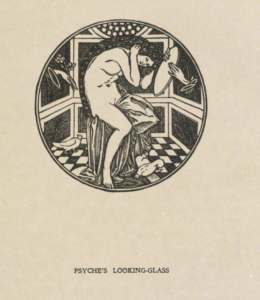

Artwork In The Venture

The artwork that appears throughout The Venture must be mentioned in any discussion of feminism at the fin de siècle. Presenting women in such a vulnerable state is not acceptable in today’s society, in addition to being frowned upon. “The obsession with sex at the fin de siècle was vividly expressed [through] the artwork,” and continuous to play a part in determining the viewpoints society held on women (Zastre, 2019). Artwork in The Venture including Psyche’s Looking Glass, Pan and Psyche, and the Queen of Fishes are among the few illustrations in the magazine which sexualize and depict women in a vulnerable state. In particular, Psyche’s Looking Glass shows a nude woman gazing intently at her reflection. This image alone demonstrates how society expected women to focus and obtain their beauty, while only being valued through their outward appearances. When analyzing the fin de siècle, the ‘New Women’s’ movement, and the way society perceived women, it is seemingly impossible to neglect the apparent perception through artwork.

Final Thoughts

“The belief that a women’s primary role was to be a wife and mother, was itself in crisis, and femininity was undoubtedly questioned in new ways at the fin de siècle” (Roberts, 2). Women in London fought for additional rights, including the ability to vote, as well as for society to see them for more than just their domestic responsibilities and outward appearances as the gender roles were being questioned as society transitioned out of the Victorian Era. Furthermore, despite the fact that John Masefield’s contribution to The Venture is sometimes disregarded in favour of his more well-known work, it exemplifies important ideas regarding how women were viewed at the turn of the century. By highlighting that women are more than simply their appearances in the first poem, Masefield illustrates the transition toward the “New Women” movement. In contrast, Masefield rejects this notion in his second poem by adhering to the societal expectation that women are solely valued for their outward features. Additionally, the magazine’s artwork accentuates the notion that women’s contributions to society derive from their attractiveness regardless of how untrue this assumption is. In general, because society still denigrates women and because the issue of women’s rights is constantly being challenged, it is critical to examine how society viewed women through literature and art in the years before the Canadian suffragette movement in order to prevent similar treatment of women in the future.

Work Cited

- Barrett, Kara L. “Victorian Women and Their Working Roles.” Buffalo State University , State University College at Buffalo, 2013, pp. 1–1.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “John Masefield”. Encyclopedia Britannica,28 May. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Masefield-British-poet. Accessed 29 November 2022.

- Gavin , Adrienne E. Writing Women of the Fin De Siècle: Authors of Change. Scholars Portal, 2011.

- Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the “Fin De Siecle”. Manchester University Press, 1997.

- Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl, and Lynne Pearce. Feminism and Women’s Writing, Edinburgh University Press, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central,https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ryerson/detail.action?docID=5400116.

- Masefield , John. The Venture , 1903, pp. 1–74.

- Prystash, Justin. “Sexual Futures: Feminism and Speculative Fiction in the Fin De Siècle.” Science-Fiction Studies, vol. 41, no. 2, 2014, pp. 341, doi:10.5621/sciefictstud.41.2.0341.

- Richardson, Angelique, and Chris Willis. The New Woman in Fiction and Fact: Fin-De-Siècle Feminisms. Palgrave, 2002.

- Roberts, Mary Louise. Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in Fin-De-Siècle France. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Young Lim, Kee. Cultural Politics at the Fin De Siècle. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Zastre, Sydni. “’The Erotic Work of Art Is Also Sacred’.” Constellations, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019, https://doi.org/10.29173/cons29387.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.