Exploring Neopaganism and Feminist Theoretical Viewpoints In William Sharp’s “The Black Madonna”

Introduction

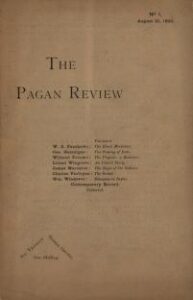

In this exhibit we will be discussing “The Black Madonna” written by William Sharp. Which is a short story published in the avant-garde magazine The Pagan Review. At the time, the magazine was intended to promote the concept of “New Paganism” and was sought out to explain any misconceptions about what paganism actually is. He sought to inform the readers about history, spiritualism and other mystical practices, also referred to as “pagan beliefs,” which were not usual at the time, because the majority of people already followed traditional religious beliefs. Albeit his most riveting short story from that magazine being “The Black Madonna” a common figure that notably exists in patriarchal religions, such as Catholicism, mainly due to her historical roots and what she represents (Michello 2). This short story represents elements that are prevalent throughout the whole magazine such as decadence, neopaganism, feminist ideologies and spiritualism, which is heavily contributed throughout much of his Sharps Works. This Exhibit will center on and analyze William Sharp’s short story The Black Madonna and how this text coincides with themes of Paganism, feminism and religious beliefs. While exploring how all of these contribute to the ideology that “The Black Madonna” who was an “intersect of gender and race” (Michello 1), was a way to symbolize these Pagan ideologies and adopt these feminist theoretical viewpoints throughout the text.

William Sharp

The oldest of eight children, William Sharp was born in Paisley, Scotland, in 1855. The West Highlands, where the family spent their summers, held a special place in the heart of his merchant father (Denisoff, 2010). Sharp in his adolescent went on to study at university, taking an interest to poetry, philosophy, occultism and folklore (Denisoff, 2010). His keen interest on these areas of study resulted in him putting out works that related to pagan ideologies, the occult, while exploring religious beliefs and steering away from being seen as socially acceptable. Author and editor of The Pagan Review Sharp, William Sharp published this periodical in August of 1892. (Denisoff, 2010) During the time the magazine was released, it was not seen as something of considerable importance. The Pagan Review presented itself as a periodical that was purely literary, not a philosophical, partisan, or agenda-based periodical (Coste 19). Also lack of aesthetics, visuals and overall appearance of the magazine, did not contribute to the magazine’s success. However, for William Sharp, this magazine executes the vision he sought out to achieve. Thus, making this his largest and arguably best work in regard to the idea of paganism, and ideology surrounding religion, while tackling the shift from social norms in society (Denisoff, 2010).

The symbolic meaning of “The Black Madonna”

A prominent figure in many patriarchal religions, the traditional cult of The Black Madonna is usually portrayed as the fair complexed mother of Jesus, with the darker complexion of The Black Madonna, with the latter of her skin colour being notably absent in catholic church portrayals (Michello 1). In many religious contexts The Black Madonna lacks recognition due to the intersect of her gender and race and this absence is especially notable in patriarchal religions, such as Catholicism, because of her historical roots and what she represents (Michello 1). The Black Madonna is the embodiment of strength and power, in contrast with the traditional depictions of Mary who has a fair complexation and is seen as nurturing and obedient (Michello 1). In William Sharps short story “The Black Madonna” he touches on pagan rituals while exploring the symbolic of The Black Madonna, being this safe haven. Throughout the story, many men and women worshipped and would seek a “vouchsafe” from her, hoping for grace and granting permission they would chant:

O Mother of God! O Slayer! be merciful! Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity [upon us!

Be merciful, O Queen!

Hail, Giver of Life and Death! (Brooks).

This text seems to support feminist theoretical viewpoints as well as religious beliefs, where she is viewed as this figure representing the “Mother of God” “Sister of the Christ” and “The Bride of the Prophet” and also referred to as queen multiple times throughout the text (Brooks). She embodies these figures that have importance in religious contexts, that people gravitate towards in times of guidance. When analyzing the text William Sharp portrays her death in a drastic way, to the priests who once looked upon her for guidance, the priest is the one who ultimately burns her at the stake. This may signify his neopaganism views by not embracing religion, and instead she perishes just like what she stood for and represented: “If ‘The Black Madonna’ can be described as a short story featuring pagan elements, fateful love and exoticism, mixing the religious and the profane, beauty and death, it is also a proto-whodunit steeped in indeterminacy, leaving the reader to decide whether god or a god exists or not, among other questions” (Coste 24).

Many times, throughout the text The Black Madonna is seen to be in fear of what’s to come, and horrible cries when she ultimately perishes, which ultimately shows her as being weak and instead a mortal. The Black Madonna is shown facing these trials and tribulations where she screams to be freed from the agony: “in the hunger of his desire she sinks as one who drowns” (Brooks). Which raises the question if God could truly save you, why didn’t The Black Madonna save herself from this hell. Another form of mockery against her statue can be seen in the text: “As he finisheth he turns towards the great Statue of the Black Madonna and, laughing, hurls his spear against its breast, whence the weapon rebounds with a loud clang” (Brooks). The priest is seen committing an act where he devalues what The Black Madonna stands for, which can be a representation of religion as a whole. Bringing forth the idea that religion cannot save you.

Feminist Viewpoints

In adopting the idea of neopaganism Sharp developed a modern take on topics that were seen as taboo, especially his take on feminist-based viewpoints: “Another feminist view is that it is not that religion is the cause of women’s oppression, but rather the interpretation of religious beliefs by men in positions of power who explain religious ideology to benefit themselves” (Michello 3). Through many of Sharp’s writing, it can be interpreted that he viewed men and women as a whole, which many see as female liberating. In adopting neopaganism it allowed him to refrain from religious beliefs, and instead insert his own ideologies on women’s rights, thus allowing him to be more open in his works. Many of Sharp’s ideologies and way of thinking can be seen as having a modern take on women’s rights, which was not the norm for his time period. Many of his works were published during the late 19th century, which was a period were women were not allowed a lot of freedoms. Notably, His pseudonym of Fiona Macleod allowed him to step into the role of a woman and have this feminine point of view, in order to showcase these values and beliefs through the writing of a female (Denisoff, 2010). In creating works such as The Black Madonna it allowed for women to be seen in a different light and Although, Sharp uses this short story to touch on pagan rituals, it can be interpreted to be a text of female praise and honour. This text seems to support feminist ideologies, and support women’s rights.

In conclusion…

The Black Madonna was one of Williams Sharps works, that had a feminine viewpoint, while pushing forth the idea of neopaganism. Sharp’s depiction of the Black Madonna is an allegory for how the downfall of women, can ultimately come at the hands of men, while going unnoticed of the power and strength that they possess. In many of Sharps work he adopted this attitude of not being seen as popular due to the nature of his periodicals. He refrained from religious ideologies and instead adopted this new outlook on paganism, that allowed him to explore these new mediums that were seen as blasphemous during the nineteenth century.

Works Cited

Brooks, W. H. “The Black Madonna” The Pagan Review, 1892, Yellow Nineties 2.0, p. 5-18.

Coste, Bénédicte. “Late-Victorian Paganism: The Case of the Pagan Review.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, no. 80 Automne, 2014, pp. 2.

Denisoff, Dennis. “William Sharp [pseud. Fiona Macleod, W.H. Brooks] (1855-1905),” Y90s Biographies, edited by Dennis Denisoff, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0, General Editor Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/sharp_bio/.

Michello, Janet. “The Black Madonna: A Theoretical Framework for the African Origins of Other World Religious Beliefs.” Religions, vol. 11, no. 10, 2020, pp. 511. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/black-madonna-theoretical-framework-african/docview/2550243309/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100511.

The Pagan Review (Aug. 1892). The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. Dec. 26, 2011. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=TPR.htm

Willburn, Sarah A., Tatiana Kontou, and Taylor and Francis eBooks. The Ashgate Research Companion to Nineteenth-Century Spiritualism and the Occult. Ashgate, 2012

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.