Queerness and Religion in the Victorian Era: The Dial, Vol. 1, The Cup of Happiness

Introduction

In my research, I delved into The Dial, Volume 1, looking at the work titled “The Cup of Happiness”, which I took a deeper look at the allusions and symbolisms made in “The Cup of Happiness”. I believe that these references create a specific narrative that implies that the character— the Prince, is queer. However, this narrative also serves as a comment on queerness and religion in the Victorian Era through the Prince and the short play that follows in “By Way of Prologue”.

CHARLES RICKETTS’ PERSONAL LIFE

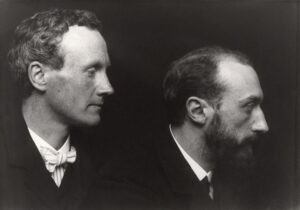

Charles Ricketts was a British artist, who worked alongside his lover, Charles Shannon, another British artist. Together, they created the initial number (Volume 1) called The Dial (Clark, 33), Ricketts illustrating several of the pieces featured in the aforementioned work, but little to none of the Victorianists know about Charles Ricketts (Weltman, 574). Yet, despite being the life partner of Shannon, Shannon had affairs with women and even thought about marrying them (Cook, 622).

ANALYSIS— CONTEXT FOR BY WAY OF PROLOGUE

“The Cup of Happiness” begins with a long narration, which provides context to the play introduced in “By Way of Prologue”. The speaker states that “it is a play, and not a medicine after all, my Cup of Happiness; not an elixir, a cure for the liver” (Ricketts, 27). This line can be interpreted as “it’s not medicine, it’s a cure for my anger/wrath (emotions).

The symbolism of the liver derives from the mythology of Prometheus, where he was punished for providing fire to the humans (out of his love for them), having a vulture peck at his liver each time it grew back, implying that the liver is a symbol of his love, or in more general terms, his emotions towards the humans. In the context of the story, it alludes to Rickett’s feelings on the matter, that this piece is meant to serve as his comment on queerness and religion, that it is the “cure” for his “liver”.

Ricketts invokes Madam Thalia, one of the muses in Greek mythology, who specifically oversaw comedy and idyllic poetry. Muses are inspirational goddesses of literature, science and the arts. They’re considered to be the source of knowledge embodied in poetry, lyric songs and myths in ancient Greek culture.

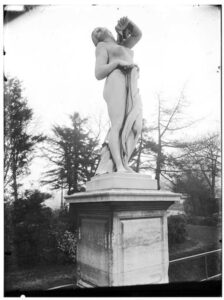

Considering that Madam Thalia is a goddess that presides over comedy, and that Ricketts has already made a reference to La Comédie humaine, it may imply the fact that she is La Comédie humaine in this story, along with the fact that Madam Thalia is often portrayed with a laughing mask in her hand. From this idea, and the implication of the juxtaposition of the garden and the statue, it suggests that this supposed “comedic” story is actually a tragedy. The speaker labels the garden with happy, and positive connotations, where it is described as a “bright garden”, countered by a statue of La Comédie humaine, described as “strange” and “bitten to death”, amongst the “bright” garden, which is alluded to be the Garden of Eden.

Ricketts references Schumann (Ricketts, 28), whose full name is Robert Schumann, a German composer (1810-1856), and is considered as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic Era. The speaker states that Schumann saw Thalia/La Comédie humaine break her mask, and thus has a feeling of empathy. The passage ends with the word “warum”, meaning “for what purpose”, and in this context, it can be assumed that Ricketts is asking “for what purpose would Schumann feel empathetic?” (Ricketts, 28).

There is a lot of repetition of the word “warum” (Ricketts, 28)— a German word in the prequel of the “By Way of Prologue”. When translated into English, it equates to the meaning “For what purpose”. Thus, when Ricketts conveys the idea that Schumann’s “warum song” (Ricketts, 28) is in a minor key (minor songs typically imply sadness or a negative emotion), it can be assumed that the song implies frustration, and hopelessness.

The narrator says for Venus-Aphrodite to continue “mercifully wring the glittering drops from [her] mane”, into the Cup of Happiness. BUT if it ended up being Eve, then she would not wring into the cup. Note how it is not the narrator themselves that does not want Eve to “wring”, as the diction would have changed to provide a personal pronoun such as “my Cup of Happiness”, to state that it is the owner of the cup themselves that does not want Eve’s “glittering drops”. Rather, Eve herself does not want to do so.

Considering that Eve is known as an important figure in the Bible, it implies that she does not accept all forms of love in terms of religion, while Venus- Aphrodite does, since she is a goddess of love, beauty and sexuality, which implies acceptance. This juxtaposition of two major figures and their symbolism hints at the topic of queerness covered in “The Cup of Happiness”.

The narrator holds Venus-Aphrodite in high regard, describing her qualities as “beautiful”, “sweet and gracious” and that her bubbles were “bright” and “chiming”, not to mention her drops were “glittering”. However, on the opposite end, when Eve is brought up, he states “but, Eve a Jewess”, the diction of “but” almost sounds as if the narrator is being weary, as it is followed by a descriptor. However, the speaker still regards her, in a biblical perspective, beautiful, naming her tresses “splendid”.

Rickett’s references to the Bible— the virtues in particular, uses personification. The speaker notes that “virtues… cannot bend their limbs”. By personifying the virtues and providing them with human qualities, Ricketts is able to assign negative connotations, as if the virtues themselves are to some extent, sinful, as humans are able to sin as well. In this context, this personification suggests that religion’s rules— or virtues are steadfast and have no exceptions, therefore, their “limbs” can’t “bend”. It is without a doubt that strange behaviour such as “intercourse with other males, with a particular gendered behaviour… was seen as morally degenerate” (Elfenbein 538) in religious context.

ANALYSIS— BY WAY OF PROLOGUE

In ”By Way of Prologue”, the Prince is surrounded by lavish items such as “bon mots” being “printed on pink paper… trimmed with lace designed by the best artists”, revealing that there is decadence at play, surrounded by beautiful artistry, yet is unhappy. This aspect is exaggerated further, where he laid on “princely cushions, on a golden and orthodox couch”. Ricketts also uses the word “orthodox” several times while describing his room, further exaggerating the idea of people sticking to religion, that everything in his room is considered as “orthodox”.

Most importantly, there is a painting in his room that depicts the “virtues each overcoming a dragon… holding a hall-marked Cup of Happiness” (Ricketts, 29), signifying that all of the orthodox, and virtuous items he has should be able to fulfil his Cup of Happiness.

Ricketts directly states that “the allegorical twist of the enamelled and painted dragons” (Ricketts, 29) has a hidden meaning with the diction “allegorical”. These dragons appear to represent repressed feelings that should be denied or shunned by Catholics, with the “enamelled” state of the dragons with a clean, shiny cover implicating that the “dragons” should be defeated by being locked forever with the “enamelled” casing they are imprisoned in.

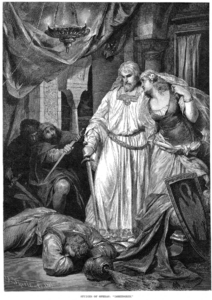

Queerness in the Prince is further implied with the allusion to “Lohengrin” (Ricketts, 29), a Romantic opera that is most notable for the tune of “Here Comes the Bride”. This reference strongly suggests a wedding is occurring between the Prince and a woman. Yet, the contrast between their feelings on the matter is apparent. As they both have a celebratory drink on the occasion of being wed, the woman is depicted with positive connotations when drinking the wine, the “gummy liquid… at her touch, glowed, bubbled, throbbed and rose passionately towards her” (Ricketts, 29), relishing at the fact she is now married. However, when the Prince drinks the wine, “it sweeps through… [his] veins, dancing and seething there” (Ricketts, 29), the diction of “sweeping” and “seething” making it appear as though the Prince did not consent to being wed, and the wine in his veins are “seething” due to being angry at the situation. The Prince is now a King.

ANALYSIS— THE PLAY

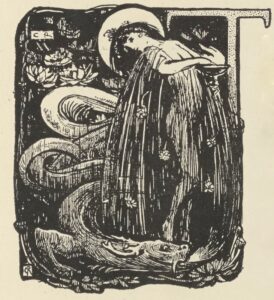

Ricketts introduces the characters: Palm-tree, Lightning, Thunder, Monster, Fantasy and the Prince. Although these characters may initially appear to be conversing with one another, their dialogue implicates that these characters are a representation of someone’s mind. The character, Thunder, has a line that introduces a break in the Fourth Wall, asking “How came you [Lightning] in this scene”, followed by “we are in an imaginative landscape” (Ricketts, 30). Since the Thunder seems to be self-aware with fourth wall breaking comments, this “imaginative landscape” can be assumed to be the individual’s mindspace, where these characters are conversing.

In this play, the Palm-Tree represents the individual’s belief in religion, noted by the character describing themselves as “a symbol of virtue” (Ricketts, 30), and since a tree has very strong roots to keep them grounded, it is hinted that the individual is firmly “rooted” in their beliefs. The Lightning portrays someone’s impulses and desire, hinted by the notes, which state that the Lightning is indulging in “levity” (Ricketts, 30). The Thunder symbolises one’s reasoning, which always trails behind Lightning. The Monster is alluded to be a representation of queerness, denoted to have a “thorn quite thoroughly into his right paw” (Ricketts, 31), and is explicitly stated to be a homosexual man noted by the “full and fruity a sound” (Ricketts, 31) when speaking to the Prince. Fantasy is a representation of religion in the Victorian Era, where the Prince appears to be the prime of The King’s life, not tied down by marriage.

The characters dialogues further implicate the Prince— who is now The King to be queer.

Lightning notes that “thorns and snakes are a great mistake in nature” (Ricketts, 31). This line calls back to the Monster’s description as they have a thorn stuck “thoroughly into his right paw”. The thorn also symbolizes sin, suggesting that the Monster is considered to be a sinner for their queer tendencies.

The Palm-Tree backs this idea by saying “let us [Lightning and Palm-Tree] form a society to suppress them—and immodest literature” (Ricketts, 31). The “them” references not only the Monster character, but dehumanizes queer people in general with an “us vs them” analogy.

Ricketts creates a perverse version of Eve, naming the Fantasy character “Lilith”, meaning “night monster” who is known for betraying Adam in the Bible, not wanting to be beneath him. Due to the perversion of Eve, it implies that Ricketts views religion as monstrous, having such strict beliefs and wanting everyone to conform to their beliefs, to the point where Ricketts chooses to make fun of Eve, making her appear as an “evil” character. Fantasy goes out of her way to entice the Prince, to become one of her many lovers, kissing “her hand to the Prince, who (Fantasy) leans against the Palm-Tree… beckons to him.” I believe that this is a reference to Shannon’s affairs with women, the ladies enticing him to become their lover. In this context, Ricketts portrays the only female character in the play as evil, due to the affairs.

Towards the end, the characters begin to break the fourth wall. The Monster notes that “The Cup of Happiness will be compromised” (Ricketts, 33) with Fantasy managing to make “the whole stage look shocked” (Ricketts, 33), suggesting a mental breakdown not only amongst the cast, but even the “imaginative landscape” itself, the limelight “blushing” at her remarks of shunning the Palm-Tree for being married.

CONCLUSION

At the end of The Dial, Ricketts outright states an apology, that their work may or may not be “orthodox”, as the goal was attempting “to gain sympathy with its views” (Ricketts, 36) with works of melancholy, which “The Cup of Happiness” is an example of. Queerness and religion in the context of the Victorian Era depicts a bitter relationship, with religion having such a strong hold on the Victorians, that the term “closet” began to be associated with the definition that it was an identity to be hidden from the public (Malley, 543). With the allusions made to Greek and Roman gods and goddesses, to composers, popular operas in the Romantic era and symbolic references to the Bible, the fear of being shunned by the Catholics perhaps inspired those with queer tendencies to shy away from ever explicitly acting upon their desires.

Works Cited

Clark, Petra. “Bitextuality, Sexuality, and the Male Aesthete in The Dial: “Not through an orthodox channel”.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 56 no. 1, 2013, p. 33-50. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/493237.

Cook, Matt. “Domestic Passions: Unpacking the Homes of Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 51, no. 3, 2012, pp. 618–640., doi:10.1086/665270.

Elfenbein, Andrew. “Byronism and the Work of Homosexual Performance in Early Victorian England.” Modern Language Quarterly (Seattle), vol. 54, no. 4, 12/1993, pp. 535-566,doi:10.1215/00267929-54-4-535.

O’Malley, Patrick R. “Epistemology of the Cloister: Victorian England’s Queer Catholicism.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 15 no. 4, 2009, p. 535-564. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/316565.

Weltman, Sharon Aronofsky. “The Art of Charles Ricketts: Selected Writings.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 58 no. 4, 2015, p. 574-578. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/582577.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.