Judeo-Christian Influences on the Attitudes Toward Infant Death: Leslie Moore’s “Will o’ the Wisp”

© Copyright 2023 Nora Dempsey, Toronto Metropolitan University

❈ An Introduction to Leslie Moore’s “Will o’ the Wisp”: A Short Story ❈

Published in the fifth edition of The Green Sheaf in 1903, Leslie Moore’s “Will o’ the Wisp” is a short story that follows a young boy being haunted by his baby sister who was unbaptized when she died. She visits him every night as a will o’ the wisp – a small dancing flame, usually observed in swamps and marshes, and sometimes described as dangerous; as a “harbinger of bad news and death” (Edwards 3).

However, will o’ the wisps are not always considered dangerous and bad. Some say that will o’ the wisps are the souls of the unbaptized, only aiming to play tricks on travellers, never aiming to harm (Feilberg 298). The boy watches through his bedroom window and follows his sister outside, calling after her; “little baby, I am watching. Oh! Do you hear! I am watching” (Moore 14). The young boy cannot communicate with his little sister as she disappears, leaving him deeply disturbed and alone in the darkness of the night.

In this story, Moore emphasizes the Judeo-Christian influence of baptism throughout the 19th century and considers how these religious ideas impacted attitudes and feelings of dissatisfaction toward the commonality of child death. The story explains that the young girl died before she could even be named and that the boy’s mother cries when the baby is mentioned. Her brother calls her a “wandering soul” (Moore 13) and tries to offer her comfort but does not succeed. The text highlights that throughout the 19th century, children dying before baptismal rites were fulfilled left families distraught as it was believed that without baptism, one could not reach salvation and remained stuck in ‘limbo.’ Limbo is described by the New Catholic Encyclopedia as “the place or state of infants dying without the Sacrament of Baptism who suffer the pain of loss but not the pain of sense” (Kennedy 238). The idea of limbo was first created and considered in the Middle Ages by St. Thomas Aquinas (Murphy 410).

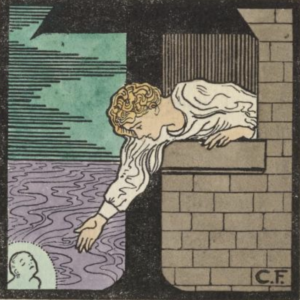

This exhibit aims to highlight how and why Moore’s “Will o’ the Wisp” acts as a commentary on the emphasis in 19th-century society of Catholicism and Judeo-Christian beliefs – such as the idea that baptism is the only way for one to reach eternal salvation. The text’s emphasis on the little girl dying unbaptized and returning as a “wandering soul” (13) to visit her brother works to dissect how harmful the pushed rhetoric of baptism, the state of limbo, salvation, and original sin were to grieving families of unbaptized children. This exhibit also includes images throughout; Figure 1 is the illustration by Cecil French of the young boy in the story reaching for his ghostly sister down below in the swamp. This illustration is included on the first page of Moore’s short story in The Green Sheaf. Cecil French also illustrated the other photos present throughout the entirety of the 5th edition of the magazine. This paper will emphasize other reactions and attitudes toward the commonality of child death throughout the 19th century, such as the creation of comfort stories and cilliní burial grounds.

❈ About the Author ❈

Formerly Ida Constance Baker, Leslie Moore – often shortened to L.M. – wrote for The Green Sheaf only once. There is little information on her life besides her close relationship with Katherine Mansfield, the famous modernist New Zealand author. The two women grew up together in childhood and attended London’s Queens College together. It is speculated that these women were in a romantic relationship during young adulthood before Mansfield married her husband, John Middleton Murry. Following Mansfield’s death, Moore published Katherine Mansfield: The Memories of L.M., an intimate recount of Mansfield’s life and death, “watch[ing] Katherine’s compulsion to discover herself and to live life to the full; she witnessed the disastrous first marriage, the coming of John Middleton Murry, the fight against illness—and the growth of Katherine Mansfield as an accomplished writer” (Moore). This book was Moore’s final work, published in 1971. In addition, both Mansfield and Moore were close friends with Pamela Colman Smith, creator and editor of The Green Sheaf, who was also speculated to have been queer and was an influential feminist, decadent artist and author of the late 19th century.

❈ Infant Death & Comfort Stories ❈

Comfort stories, defined as “[stories] that framed deaths of children as great and unique tragedies” (Gryctko 293), were created as a reaction to the fear of the alarming rates of infant death throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Children dying in infancy was a common experience for families; many children died unbaptized shortly after birth causing a wide range of fear instilled by overpowering Judeo-Christian ideas of the 19th century. Comfort stories center on the experience of a deceased child as passive, forever innocent, unchanging, and forever possessable; comfort stories are written for grieving parents, acting as a comfort that their child is forever in their most ideal childlike state. John Hopkins scholar Mary Gryctko describes that the children in these comfort stories are “made into objects rather than people, dead children fulfill the need for a stable, unchanging model of childhood in ways that living children cannot” (292). Gryctko also draws on the privilege and sublimity of sorrow in the death of children, exploring how the writing of comfort stories allows one to “prolong and preserve the “luxury of weeping” and the “grief most sacred” (304).

Moore’s story does not end in an ideal manner; the boy is left crying all alone in the darkness, confused and distraught over his baby sister appearing to him briefly as a will o’ the wisp, only for her to disappear when he gets close to her. However, “Will o’ the Wisp” has considerable features of a comfort story. The little girl is forever frozen in her child form as a will o’ the wisp and does not harm her brother. It appears as if the little girl visits her brother only to let him know that she is there. There is an interesting juxtaposition between will o’ the wisps being considered harbingers of bad news and death, and the little girl frozen in time forever as a baby. The little girl’s return can be interpreted in a few different ways. On one hand, the girl potentially visits her brother to warn him of something – perhaps the warning of his own death or that she is stuck in an in-between state of life and death such as limbo. On the other hand, she may visit to offer him comfort that she is okay, she is unchanging and forever innocent. Her visits may only come to offer joy and that she is still around, as she has not been able to move onto the afterlife. As will o’ the wisps are considered to be the souls of the unbaptized (Fielberg 298), maybe that is all her visits are; a call to her brother that she will be around for some time, as her missing baptismal rites prevent her from moving on to something of heaven or salvation.

The fear that a child would not reach heaven if they died before baptism alarmed families, worrying that their child would end up in damnation or limbo. Comfort stories, such as “Will o’ the Wisp” offered consolation to 18th and 19th-century families that their children at the very least remained in their childlike state after death, forever “pure and helpless” (Gryctko 306). Comfort stories offer a unique perspective on the loss of infants, providing families with the small joy of considering that their child will forever remain in childhood.

❈ Cilliní Burial Grounds as a Response to Fear & Judeo-Christian Definitions ❈

Along with the creation of comfort stories as a way to come to terms with the tragedy and commonality of infant death in the 19th century, cilliní burial grounds were also created and used to comfort families dealing with infant death in England and Ireland. First created in the 15th century, these burial sites were often placed on the grounds of abandoned churches and graveyards, used for the burial of unbaptized children, the disabled, and those who had committed suicide (Murphy 409). As the Catholic Church identified baptism as a requirement to cleanse the soul of original sin, children who died before this sin could be washed away were not permitted to be buried on consecrated ground. Original sin is also defined in the New Catholic Encyclopedia as:

“(1) the sin that Adam committed; (2) a consequence of this first sin, the hereditary stain with which we are born on account of our origin or descent from Adam” (Catholic.org).

Original sin is quoted in the Bible numerous times, notably in Romans 5:12:

“Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned” (Romans 5:12, ESV).

The concept of “original sin” has been painted numerous times. Figure 2 details Cornelis van Haarlem’s “The Fall of Man” painted in 1592. The first human sin was the eating of the apple in the Garden of Eden by Adam and Eve. Original sin is therefore the sin all humans have within them, as Adam and Eve did.

Based on original sin, the idea of limbo acting as a state one resides in if their original sin is not washed away offered both comfort and concern to grieving families, knowing that their children would be provided with “a means to reconcile the problem of what happened to the souls of those who—through no fault of their own—were barred from heaven” (“Limbo,” NewAdvent). Archaeologist and scholar Eileen Murphy described limbo as “a kind of in-between state, neither the happiness of heaven nor the torments of hell” (410). Cilliní burial grounds offered some consolation to families not permitted to bury their loved ones on Catholic sacred grounds and allowed them to consider that their loved one would avoid hell and damnation because they were buried in a partially recognized Catholic cemetery.

The fear instilled by the Church of a child ending up in limbo and unable to reach salvation also influenced the timing of baptism. At the end of the 19th century, one in ten children died in the first year of birth in Ireland (Kennedy 241). In response to these alarming rates of child death, emergency baptism was often completed by doctors and nurses; an emergency baptism could even be performed while the child was still in utero. Early baptism was essential to parents in late 19th-century communities as the fear of a child dying unbaptized not only left them feeling unsatisfied but brought upon the fear of God– the fear that their child would never be able to reach heaven, the ultimate end goal of life. Figure 3 is a plaque at Ridds Green cilliní burial ground located in County Wicklow, Ireland. The plaque reads “cillín children’s burial ground. This area is known as Ridds Green” (Fig. 3). Many of these plaques exist today as there were thousands of cilliní burial sites throughout Ireland and England created in the 18th and 19th centuries. These plaques remain today as historical sites and as a reminder of what the land was once used for when child death was incredibly common.

Although it is not specified whether the young girl was buried in a cilliní burial ground in Moore’s short story, cilliní burial grounds were used as a means to offer comfort to families. A child being buried in a cilliní graveyard offered some consolation of avoided damnation, and comfort stories explored what the child experienced after death – the deceased would forever remain as a child. The creation of cilliní burial grounds speaks to how desperate families sought assurance that their child would have some chance at happiness, even if it meant they would remain stuck in limbo; at the very least it meant that the child would avoid damnation. Additionally the idea of limbo conjuncts with the context of what comfort stories did for families of the 19th century who were struggling with infant loss. If nothing else, an unbaptized child would forever exist in limbo as a child, preserving the child as a precious and unchanging object (Gryctko 295).

❈ Conclusion: Moore’s Critique of Religion and Fear ❈

Essentially, Moore’s short story acts as a commentary on the fear that was instilled by the Judeo-Christian idea of baptism and the importance of being baptized when one dies. “Will o’ the Wisp” acts as a comfort story as it keeps the young girl in her purest, most helpless state as a baby. This story’s content is grim at first glance. The boy cannot communicate or touch his baby sister, which is unsettling to both him and the reader. However, the child remains in her form as a baby in what is considered limbo and as a will o’ the wisp. In the understanding of what ‘limbo’ and ‘will o’ the wisp’s’ are, this means that she has avoided damnation and can return to her brother to remind him that she is still there, forever his baby sister. Moore’s emphasis on the unbaptized aspect of the child acts as a criticism of the Judeo-Christian need for baptism to reach salvation. When a child died unbaptized in the 18th and 19th centuries it was understandably devastating for families. Responses to the fear of dying unbaptized were all-encompassing – from literature to separate burial grounds. The strong Judeo-Christian emphases on baptism, limbo, and original sin made families fear for the fate of their deceased children, making it hard to separate religion and family. Moore’s place in 19th-century society offers a first-hand account of the damaging rhetoric that baptism is the only way to reach heaven, even for babies – thought to be the purest of humanity. Moore’s use of the will o’ the wisp folktale figure works to uniquely critique larger, damaging social forces such as the Catholic church and the ideas that it pushed onto families struggling with infant loss.

Works Cited

Cecil French. “Will o’ the Wisp,” 1903, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Public Domain.

Cornelis van Haarlem. “The Fall of Man,” 1592. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Edwards, Howell G.M. “Will-o’-the-Wisp: An Ancient Mystery with Extremophile Origins?” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol. 372, no. 2030, Dec.-Jan. 2014, pp. 1-10. Royal Society Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0206. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

Feilberg, H. F. “Ghostly Lights.” Folklore, vol. 6, no. 3, 1895, pp. 288–300. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1253002. Accessed 2 Dec. 2023.

Gryctko, Mary. “The Sweetest Little Thing That Ever Died:” Nineteenth-Century Comfort Books and the Creation of the Immortal Child.” Victorian Review, vol. 48 no. 2, 2022, p. 293-308. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/vcr.2022.a900628.

Kennedy, Liam. “Afterlives: Testimonies of Irish Catholic Mothers on Infant Death and the Fate of the Unbaptized.” Journal of Family History, vol. 46, no. 2, 2020, pp. 236-55. SAGE Journals Online, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363199020966751. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

“Limbo.” NewAdvent, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09256a.htm. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023

Moore, Leslie. Katherine Mansfield: The Memories of LM. Taplinger Publishing Company, 1972. Internet Archive, Taplinger Publishing Company, archive.org/details/katherinemansfie00lmle/page/n1/mode/2up?view=theater.

—. “Will O’ the Wisp.” The Green Sheaf, vol. 5, 1903, pp. 13-14.

Murphy, Eileen M. “Children’s Burial Grounds in Ireland (Cilliní) and Parental Emotions Toward Infant Death.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 3, 2011, pp. 409–28. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41306895. Accessed 2 Dec. 2023.

“Original Sin.” Catholic Online, Your Catholic Voice Foundation, www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=8782. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

“Romans 5: English Standard Version (ESV).” Blue Letter Bible, Good News Publishers, www.blueletterbible.org/esv/rom/5/1/s_1051001. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

“Ridds Green Cillín Burial Ground,” 2021. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.