Wives, Mothers, and More: Reclaiming Identity in the shadows of Domesticity

Cult of True Womanhood

The “cult of domesticity” and the doctrine of separate spheres not only imposed selfless wife and mother roles on women but also idealized these roles, glorifying women’s ability to regulate the household and provide a haven within the home. This glorification operated on the notion that women, by nature, were inferior to men in the public sphere, political and educational sector but superior in the moral and spiritual realm. This ideology believed that women were to be protected from the outside world, solidifying their place within the household to fulfill roles deemed appropriate to their nature (Vaid 65). However, these prescribed roles severely limited women’s agency, confining them to these predetermined spheres and hindering careers and aspirations beyond the domestic realm. Frederick Greenwood’s critical essay “Women—Wives or Mothers” by a woman, highlights the prevailing societal expectations and ideologies of women during the 19th century. While Greenwood’s perspective does not align with feminist ideals, this essay aims to critique his perspective, explore societal expectations of women in the 19th century, and demonstrate women’s agency within these standards while underscoring its relevance to feminist movements like the Suffrage and New Woman movement striving for gender equality.

The Victorian era was a pivotal period in the evolving history of feminist movements, aspiring to regain agency amidst the roaring patriarchal society. This era subjugated women to domestic spheres and expected them to embody virtues of purity, piety, submissiveness and domesticity (Welter 152). This prevailing ideology underscored a clear distinction between the roles and duties of men and women, wherein men dominated the public sphere as financial providers. In contrast, women were confined to the private sphere, providing nurturance and physical comfort for their families (Vaid 64). These socially constructed norms limited women to the role of guardian of the household, where they “regulated household consumption in activities ranging from spending surplus income to organizing servants, and the ideal domestic woman used all her time to make the home run smoothly” (Boardman 150); expectations often measured by the value, harmony and virtue women provided for their families. This further burdened them with societal expectations, reinforcing their role as caregivers and nurturers. The “cult of domesticity,” a prevailing ideology during the Victorian era, encapsulated and amplified these societal expectations imposed on women. This concept originated from the evangelical ideals of the Clapham Sect in the early decades of the nineteenth century, evolving into the prevalent ideology of the middle classes by the 1830s and 1840s. Susan Zlotnick, an associate professor of English, claims that this ideology:

“figured women not merely as disembodied angels in the house but as powerful moral missionaries within the domestic realm. Women contained the potential to repair and reform not only their husbands but also the nation—as long as they remained morally intact and politically aloof, isolated from the workaday world of capitalist competition and parliamentary processes. (Zlotnick 2).

The “cult of domesticity” and the doctrine of separate spheres not only imposed selfless wife and mother roles on women but also idealized these roles, glorifying women’s ability to regulate the household and provide a haven within the home. This glorification operated on the notion that women, by nature, were inferior to men in the public sphere, political and educational sector but superior in the moral and spiritual realm. This ideology believed that women were to be protected from the outside world, solidifying their place within the household to fulfill roles deemed appropriate to their nature (Vaid 65). This construct limited women’s agency as society confined them to these predestined roles, hindering careers and aspirations beyond the domestic sphere.

Beyond the prescribed roles of domesticity, Victorian women encountered severe constraints to their rights and opportunities, resulting in a landscape characterized by systemic oppression and gender disparities. The ideology of the gendered sphere limited women’s pursuit of higher education and labour force participation. Legal impediments, particularly the Couverture law—a legal doctrine ensuring that by marriage, husbands and wives are considered one person by law—deemed husbands responsible for the maintenance of their wives and the control over their property, businesses and income (Bishop 183). By the late nineteenth century, the gendered sphere dominated married middle- and upper-class women’s education and skill training. While men were granted an advanced education tailored to the modern workforce, women were subjected to an education befitting the domestic sphere, thus limiting their job opportunities to nursing, teaching and caregiving (Brooke 28).

In contrast, although working-class women faced similar educational challenges, they had greater access to the workforce, often employed in factories and manual labour positions to contribute to their household income. Middle-class and upper-class women risked sexual stigma and loss of their social status if they pursued labour jobs, with psychiatrists like Henry Mauds-ley claiming that “the growing number of women clamouring for work outside of the home would inevitably culminate in widespread sexual degeneration” (16), believing that by going against their natural position in the domestic sphere, women will corrupt and destroy their families and threaten the reproductive health of the nation. While the societal expectations and legal restrictions shed light on the challenges faced by women during the 19th century, a more nuanced understanding of gender roles in this era is evident in Frederick Greenwood’s critical essay, ‘Women—Wives or Mothers,’ which perpetuates these prevailing standards and ideologies.

“Women—Wives or Mothers” By a Man

Greenwood as caricatured by Ape (Carlo Pellegrini) in Vanity Fair, June 1880

Frederick Greenwood, a prolific journalist and editor, embodied a conservative mindset adhering to the Victorian era’s patriarchal norms and values, most evident in his essay where the dichotomy between women being wives or mothers is a recurring motif. He argues that, by nature, women are predestined to fulfill these roles, claiming that “woman, fresh from Nature’s moulding, is, so far as first intention is concerned, a predestined wife or mother” (Greenwood 12). This ideology frames women’s identity within the narrow confines of familial duties, adhering to Victorian norms that designate women to predestined spheres, relegating their agency to the domestic realm. Greenwood’s perspective on women’s dual roles perpetuates the deterministic view of their societal position rather than celebrating their multifaceted identities and aspirations. His assertion that ‘mother-women’ marry out of an innate maternal instinct highlights his belief that women inherently know the fold where they were intended to pass (13). Even in childless marriages, Greenwood argues that women still fulfill their dormant instincts through “unlimited and universal auntdom” (14), allowing them to satisfy their maternal roles. This implies that, by nature, women are inherently predisposed to embrace their maternal instincts. Following this, Greenwood contends that the relationship between wives and husbands is transactional, with the wife feeling gratitude toward their husbands for allowing them to fulfill her true destiny. He states, “Gratitude, none the less real because unrealized, towards the man who thus enables her to fulfil her true destiny—the saving of souls alive” (13). In return, the husband benefits from the wife’s care and devotion. By “saving of souls alive” Greenwood implies that by fulfilling their roles as wives and mothers, women contribute to the spiritual welfare of those they care for (Welter 159). Greenwood further asserts that ‘wife-women’ do not possess traits of wisdom or foresight but: “Charm, beguilement, fascination of sorts, form her poor equipment for life’s selective struggle” (18). These attributes perpetuate stereotypical expectations of women that reduce their worth and individual autonomy to predefined traits of femininity. Greenwood’s perspective underscores women’s limited autonomy during the Victorian era, emphasizing qualities that align with its prevailing patriarchal standards that limit the complexities of women’s identity, goals and aspirations.

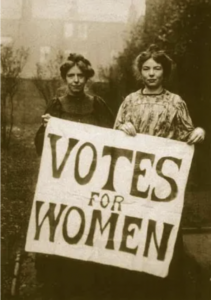

The Suffrage Movement

In analyzing Greenwood’s perspective on women, an evident disconnect and contrast occurs between his beliefs and the goals of the 19th-century feminist movements, namely the suffrage and New Woman movements. Greenwood’s dichotomous portrayal of women as devoted wives or caring mothers does not align with the movement’s multifaceted aspirations and goals. The Suffrage movement was a social and political movement advocating for women’s right to vote in political elections. The movement aimed to dismantle systemic inequalities by securing legal and political rights for women, the primary focus being on women’s suffrage—the right to have equal representation in the electoral process as men (Turner 589). Key goals within the movement were the right to vote and equal opportunities in education, employment and other societal spheres. Women aimed to challenge the notion that they were solely defined by their domestic roles and gender expectations. However, critics of women’s suffrage argued that granting women the right to vote would lead to a rejection of marriage, with concerns that neglecting their domestic responsibilities could harm their children and society, asserting, “their nervous strength in assuming new and needless duties, will they be fitted as before to enter into marriage and motherhood” (Turner 599). The quoted criticism, asserting that women will be unfit for marriage and motherhood if they engage in “new and needless duties,” aligns with Greenwood’s dichotomous depiction of women as wives or mothers. Their apprehension reflects his portrayal of women as primarily suited for domestic roles, perpetuating the resistance to women challenging gender norms, a perspective evident in his essay.

The New Woman Movement

The New Woman movement aimed to deconstruct and redefine traditional gender roles and assert women’s independence in the modern workforce (Brooke 200). Notable feminists like Amy Levy sought to declare women’s agency through her proto-feminist heroine Lyndall from her novel The Story Of An African Farm (1883). When Lyndall attends a boarding school, she realizes that gendered education aims to mould female students into reliant wives and mothers as the curriculum offers minimal support for the ambitious women seeking to pave their path in the public sphere (35). Lyndall’s rejection of the domestic ideal inspired many other Victorian feminists aiming to dismantle the domestic ideology, like Olive Schreiner, whose work also argued for the reformation of the gendered marketplace and access to the modern workforce. Like Levy, Shreiner’s feminist activism marked the beginning of New Woman literature, which “forced a discussion among late Victorians on women’s sexual and economic independence by leaving open-ended women’s narratives that push against or even transcend the domestic plot” (36). Suffragist leaders like Millicent Garrett Fawcett—president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, Jessie Boucherett and Barbara Bodichon, who helped facilitate the push through with the 1882 Married Women’s Property Act, guaranteeing wives legal property rights; Emmeline Pankhurst, who along with her daughter founded the Women’s Social and Political Union, all advocated for women’s agency within the educational, political, and public sphere to improve the status and rights of women in society (200). Greenwood’s perspective, which aligns with conservative norms, is oblivious to the demands for women’s agency and goals echoed by the New Woman movement as he deviates from feminist ideals. His emphasis on women’s predetermined roles in the domestic sphere and the transactional relationship between husband and wife reinforces the resistance to women challenging gender norms, overlooking the nuanced nature of their aspirations and goals beyond his predefined roles.

Shattering The Domestic Sphere

The examination of 19th-century societal expectations and the conservative views in Greenwood’s essay “Women—Wives or Mother” offers significant insight into the persistent struggle for women’s rights and agency. By analyzing the constraints imposed on women through “the cult of domesticity” and the gendered sphere, the essay highlights the challenges women face within the educational sector, career opportunities within the modern workforce, and societal roles. By contrasting Greenwood’s conservative perspective to the goals of the Suffrage and New Woman movements, we gain insight into the ongoing societal tension surrounding gender norms and inequalities. Pioneers within the Suffrage and New Woman movements, such as Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst, who advocated for women’s agency and rights, successfully advanced women’s employment opportunities, expanded access to education beyond the gendered confines, and increased women’s presence and participation in the political and public sectors. This analysis underscores the challenges women endured within this patriarchal society and prompts contemplation on the progress achieved in deconstructing traditional notions of femininity, motherhood and marriage. We learn to appreciate the efforts of our predecessors who made monumental strides in women’s rights, underscoring our need to continue challenging deeply entrenched societal expectations.

Works Cited

Bishop, Catherine. “When Your Money Is Not Your Own: Coverture and Married Women In Business in Colonial New South Wales.” Law and History Review, vol. 33, no. 1, 2015, pp. 181–200. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43670754.

Boardman, Kay. “The Ideology of Domesticity: The Regulation of the Household Economy in Victorian Women’s Magazines.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 33, no. 2, 2000, pp. 150–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20083724.

Cameron, Brooke. Critical Alliances: Economics and Feminism in English Women’s Writing, 1880-1914. University of Toronto Press, 2019.

https://books.scholarsportal.info/en/read?id=/ebooks/ebooks5/upress5/2020-03-02/1/9781442625600

Greenwood, Frederick. “Women—Wives or Mothers.” The Yellow Book, vol. 3, October 1894, pp. 11-18. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/YBV3_greenwood_women/.

Turner, Edward Raymond. “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 7, no. 4, 1913, pp. 588–609. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1944309.

Welter, Barbara. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 2, 1966, pp. 151–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2711179.

Zlotnick, Susan. “Domesticating Imperialism: Curry and Cookbooks in Victorian England.” Frontiers, vol. 16, no. 2-3, 1996, pp. 51. ProQuest,