The Literature Grounds are Fertile: Cross-Fertilization of Influences in “A Sonnet on Love” by Claudius Popelin

© Copyright 2024 Charles Liu, Toronto Metropolitan University

The Literature Grounds are Fertile: Cross-Fertilization of Influences in “A Sonnet on Love” by Claudius Popelin

Overview

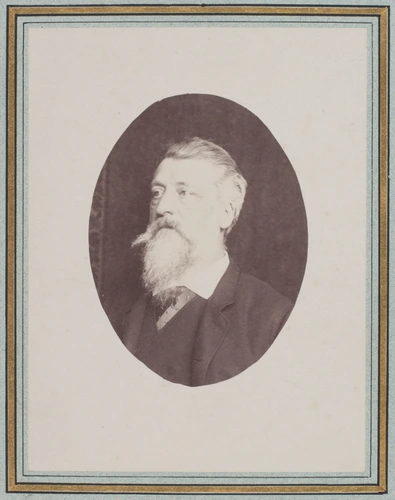

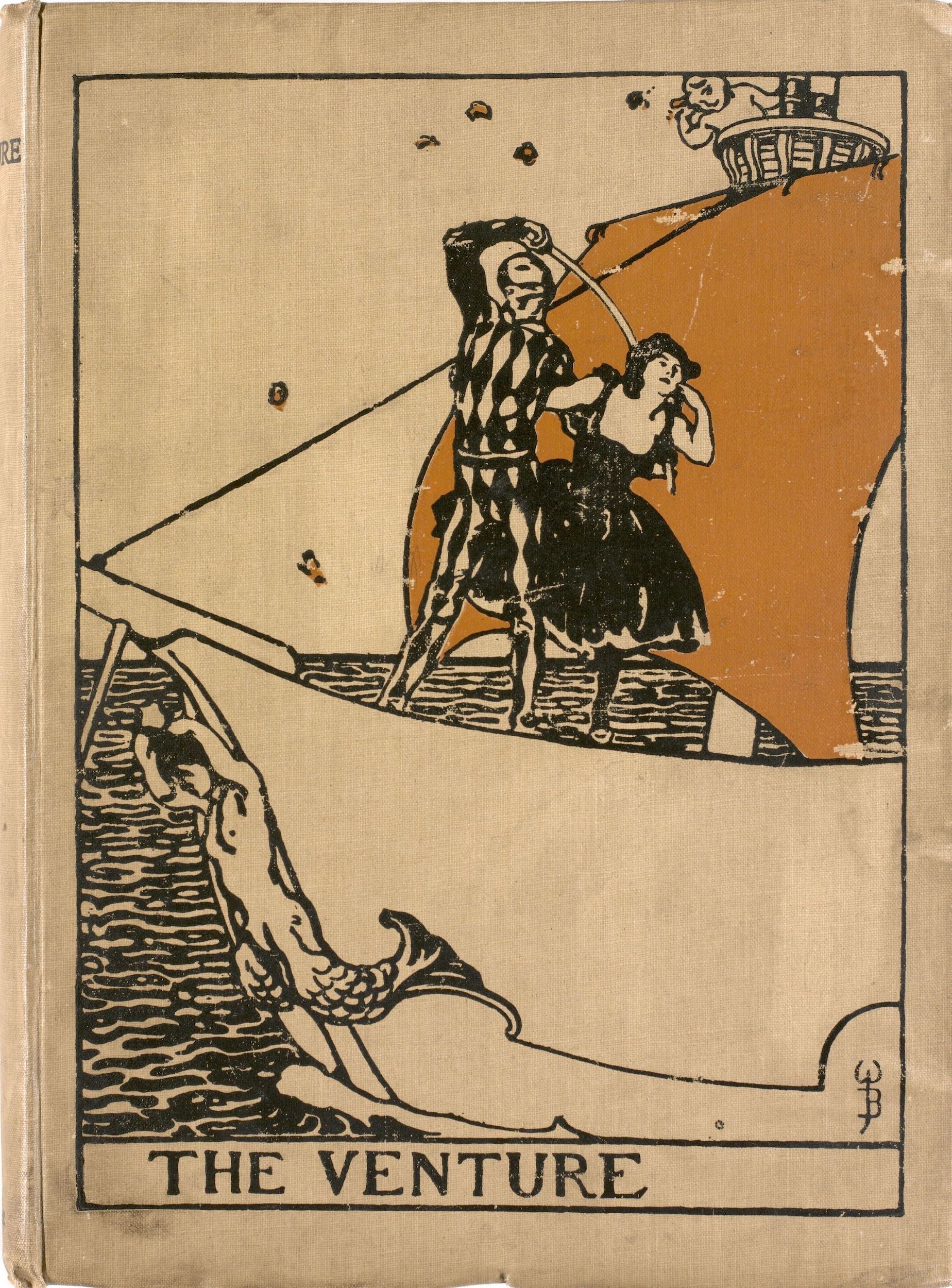

“A Sonnet on Love” not only consists of 14 lines of rhythmic poetry, but a rich historical and literary background that constitutes each word. Claudius Popelin, a multimedia artist and writer, was known for reviving “old and difficult [art] forms” and recontextualizing them in a modern context (Hobbs 389). It is no surprise then, given his artistic approach, that he approached the historically famous and onerous poetic form of the sonnet. To understand how Popelin recontextualized the sonnet, it is insufficient to simply look at one literary or social movement. Instead, there were intersecting and overlapping movements that coalesced within “A Sonnet on Love”. The fertile cross-fertilization that occurred in “A Sonnet on Love” bleeds into the Yellow Nineties in specific ways, explaining the later 1905 translation by Maurice Joy in The Venture Volume 2. This digital exhibit highlights three different movements that bear an influence on “A Sonnet on Love”: The Romantic Sonnet Revival, Parnassianism, and Gothic Literature.

Distinct Features and the Historical Context of “A Sonnet on Love”

There are two distinct features of a sonnet that are relevant to this digital exhibit.

FORM

One of the unique features of the sonnet is the form/structure it uses. The sonnet has historically employed 2 distinct and strict rhyming schemes: the Petrarchan sonnet and the Shakespearean sonnet. The Petrarchan sonnet uses a rhyming scheme of ABBA ABBA CDECDE OR CDCDCD while the Shakespearean sonnet uses ABAB CDCD EFEF GG instead (Richardson).

Another crucial part of the sonnet is the turn, also known as ‘volta’. The volta represents a turn in thinking by the poet, commonly presenting the beginning of a new perspective or solution to what was previously elaborated on. Often one syllable words such as ‘thus’, ‘but’, or ‘and’ are common indicators of the volta (Richardson). Structure-wise, the volta is meant to be found after 8 lines for the Petrarchan sonnet while the Shakespearean sonnet does not mandate a specific location for the volta (Richardson).

TOPIC

The other important feature of the sonnet is the topic. Sonnets almost always aim to praise, usually praising an individual. Historically, this meant that the sonnet was essentially a love poem, where the author would preach the beauty of someone. Petrarch was infamously hyperbolic in his metaphors of beauty, comparing women to goddesses and the sun (Steele 133). Shakespeare flipped these metaphors on its head, instead mocking Petrarchan conventions and opting for more realistic descriptors of romance (Steele 133). Overall, there is a pre-existing historical context where authors reconfigure what makes one desire another person.

It’s important to understand that Popelin did not spontaneously decide that the sonnet required revival and recontextualization. Rather, as other scholars have noted with the use of sonnets (Raymond 721, Steele 133), he is involved in a larger literary history of change and turmoil. This digital exhibit points to three particular movements that motivated the types of maneuvers and changes he made.

The Romantic Sonnet Revival and Innovation

Even though Popelin was an artist interested in utilizing antique forms, the decision to specifically focus on sonnets still remains unclear. Despite many art forms and writing conventions that would have fit his artistic style and interests, he was uniquely engaged with sonnets, writing several collections and volumes of sonnets throughout his life (Hobbs 389-40). A relevant question then is why he chose to flesh out modern influences in the sonnet form. The Romantic Sonnet Revival helps answer this question.

Often, the sonnet is proclaimed as the “most popular, enduring, and widely used poetic form” (Raymond 721). This is not entirely true. As Raymond explains, after the Elizabethan era when it had huge popularity, it went into decline and became defunct (722). This is because the extraneous and very limiting nature of the sonnet became more annoying rather than exciting. However, the “timeless appeal” that came with the sonnet became favourable as Romanticism began taking hold (721). The sonnet aligned greatly with the ideas of Romanticism such as subjectivity and emotional appeal and was thus taken up especially by women poets during the Romantic literary period (Raymond 728).

While Popelin is not a Romantic artist nor a woman, he was certainly surrounded by a strong surge of sonnets. Likewise, Popelin was not a quirky writer who was acting alone in a sonnet revival nor was he simply continuing a history of acclaim and prestige. The rise of sonnets as a popular form once again after a period of neglect was what propelled Popelin to undertake the sonnet form.

Graveyard Poetry and Love

In “A Sonnet on Love”, Popelin writes about their love in a new light. As evidenced by the request to “close thine eyes” and to “sleep / For long” (Joy, lines 1, 12-13), Popelin is not trying to do the work of praise or desire but instead trying to get the subject to sleep. Nonetheless, he does so in a loving manner, interweaving Petrarchan-like compliments such as “my charming dove” or “thine eyes so large, thine eyes so kind” (Joy, lines 1-2). The reason the subject is struggling to sleep is the persistence of nightmares or bad dreams. There are several indications in the sonnet, including the use of “golden dreams” twice (Joy, line 4, 13), to urge to sleep “softly” specifically (line 7), or most notably, the act of “guard[ing] thy flocks of dreams, upon my knees” (line 8). The shift from praising their best features to valiantly aiding them with their struggles greatly differentiates this sonnet from the canon.

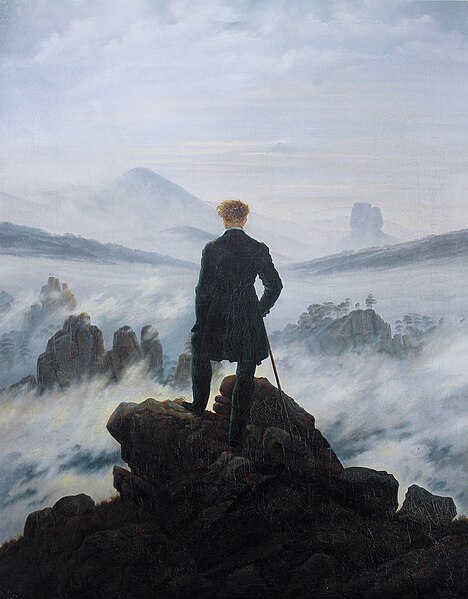

This move to a different demonstration of love is underpinned by the influence of the Gothic genre and Graveyard Poetry. As explained by Trowbridge, Graveyard Poetry was a response to the secularization around death that was a precursor to the Gothic genre (24). As notions of death shifted away from religious understandings of “a gift to the living” (Trowbridge 24), there came a deep anxiety about what comes after death. Many writers involved in this category reflected on the fact that death and the passage of time felt more troubling and fearsome. As such, there was a large emphasis on “melodramatic depictions of death and […] on the brevity of life” (Trowbridge 31). Crucially, “night, solitude and self-examination are all key tropes of the Graveyard Poetry” that necessarily arose due to the existential reflections from the Graveyard Poetry (Parisot as qtd. in Trowbridge 23). These throughlines make their way into “A Sonnet on Love” in subtle ways.

For one, there is a forced calmness omnipresent in the poem that resembles the moods invoked in Graveyard Poetry. Despite the very clear setting of a dark, windy night, there is an insistence on making such ambiance peaceful and quiet. The “gentle night” or “stars of love” speak to an implicit flip against what is commonly frightful or anxiety-inducing (Joy line 6, 11). Such resistance against fear and terror is in direct engagement with the Graveyard Poetry and specifically the imagery that runs commonly with it. Furthermore, the grief and pain that comes with adoring the subject in “A Sonnet on Love” relates to melodrama within Graveyard Poetry. For example, Trowbridge notes that secularization made a union in heaven impossible and completely changed the way love was perceived (31). The urgency in the sonnet directly relates to the growing secularization and existentialism associated with death. All in all, Popelin’s choice to focus on feelings of grief and sorrow when it is common to focus on joy and excitement was motivated by Graveyard Poetry’s similar techniques.

Parnassianism and Structure

As mentioned before, there are two common rhyming schemes in a sonnet: Pertrarchan and Shakespearean. “A Sonnet on Love” interestingly avoids both these rhyme schemes. While it uses the Petrarchan scheme by preserving the ABBA ABBA structure at the top, it diverts to a unique CCE DDE rhyming structure at the end. This allows Popelin to offer two possible voltas in the sonnet, paying homage to Shakespearean norms. While a Petrarchan interpretation makes the ninth line “And thou wilt sleep beneath mine eyes, reclining there” the volta, a different interpretation could make the eighth line “And I will guard thy flocks of dreams, upon my knees” the volta (Joy). It is very possible to read the sonnet differently because of Popelin’s structural destabilization. In the end, Popelin clearly put careful thought into the structure. The focus on not only experimenting with topic but also form can be understood as an influence from Parnassianism.

Parnassianism was an artistic movement in France that had a theory of art focused on workmanship (Robinson 739). Gautier, a prominent poet in this movement, espoused that what made art impressive and beautiful was not “descriptive or metrical virtuosity” but rather a strong attention to artistic form (738). For poetry, it was vital to maintain strong technical expertise and execution in poetry, crafting verses that were impressive and fit rhythmically.

The sonnet form could realize this ideology fully, given the abundant amount of literary references and tight form. Even if Popelin experimented with the form, he still ensured that his new form was tight and clear. There is strong musicality to the poem, and every line rhymes perfectly. As such, not only did Popelin want to recontextualize the sonnet in terms of the topic, but also the form. Parnassianism is what motivated Popelin to consider structure in his sonnet and also to ensure that it was technically impressive.

What does this have to do with the Yellow Nineties?

What is interesting about Robinson’s article is that it also fleshes out a direct relationship between French Parnassianism and English Aestheticism. For Robinson, Parnassianism was an earlier form of aestheticism that was later radicalized by the English (733). This is because Aestheticism’s claim of “art for art’s sake” stemmed from Parnassianism’s devaluation of emotion (Robinson 734). Here, a direct relationship between Popelin’s work and the Yellow Nineties is made visible. Joy possibly translated Popelin’s work to illustrate a more complete history of Aestheticism.

Furthermore, the anxiety with love and the gothic genre continued into the Yellow Nineties. As mentioned by other exhibits, the Yellow Nineties also had much writing and thinking on death, similarly questioning cultural practices and assumptions around death (Trowbridge 21). Joy’s interest in translating can also stem from a motivation to trace an earlier and different focus on such an anxiety.

Finally, the Romantic Sonnet Revival was happening primarily in England rather than France. What this means is that the relationship between England and France was not unilateral. Both countries clearly influenced one another, making their relationship much more complex. This fertile interrelational phenomenon must have had a significant bearing on how the Yellow Nineties played out and must have been of interest to Joy when translating this work.

Overall, similarly to Popelin, the Yellow Nineties was clearly influenced by several different movements. To understand the Yellow Nineties fully, it is important to turn works like Popelin as precursors and inspiration for the work that came during this period.

Works Cited

Hobbs, Richard. “Sonnets: Edgar Degas, Claudius Popelin, and the poetry of generic constraints.” Word & Image, vol. 28, no. 4, 31 Jan 2013, pp. 384-396. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/doi/epdf/10.1080/02666286.2012.740189?needAccess=true.

Joy, Maurice. “[At Twilight] A Sonnet on Love (From the French of Claudius Popelin).” The Venture: an Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 39. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2022. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/vv2-joy-sonnet.

Raymond, Mark. “The Romantic Sonnet Revival: Opening the Sonnet’s Crypt.” Literary Compass, vol. 4, no. 3, 1 May 2007, pp. 721-736. https://compass-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2007.00454.x.

Robinson, James K. “A Neglected Phase of the Aesthetic Movement: English Parnassianism.” PMLA, vol. 68, no. 4, September 1953, pp. 733-754. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/stable/459795?searchText=A+Neglected+Phase+of+the+Aesthetic+Movement+English+Parnassianism&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DA%2BNeglected%2BPhase%2Bof%2Bthe%2BAesthetic%2BMovement%253A%2BEnglish%2BParnassianism&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Ad844b23f51f67d6744be2f32144af2af&seq=4.

Steele, Felicia Jean. “Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130.” The Explicator, vol. 62, no. 3, 30 Mar 2010, pp. 132-137. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/doi/epdf/10.1080/00144940409597198?needAccess=true.

Trowbridge, Serena. “Past, present, and future in the Gothic graveyard.” The Gothic and death, edited by Carol Margaret Davison, Manchester University Press, 2017, pp. 21-33. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/stable/pdf/j.ctv18b5p6r.8.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3Ab88bff168714e934e7ca802f9e18e8f3&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1.

Richardson, Rachel. “Learning the Sonnet.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/70051/learning-the-sonnet.

Images in this online exhibit are in the public domain.