Rhetoric and Ideology in Edward Carpenter’s “The Simplification of Life”

© Copyright 2024 Abigail Apalit, Toronto Metropolitan University

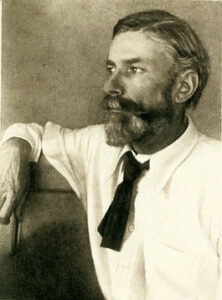

Who is Edward Carpenter?

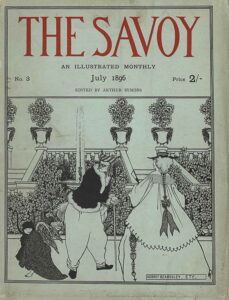

Edward Carpenter was born in Sussex, England, in 1844 to a wealthy upperclass family. He died of a stroke at the age of 84, a year after the death of his partner George Merrill in 1928 (Tsuzuki 3). Carpenter was a poet, philosopher, gay rights activist, and socialist. He fought not only for gay rights but was one of the first to challenge social and economic capitalism, and fought for clean air, prison reform, and animal rights (3). It is said that much of his socialist desire stems from his mother, Sophia Carpenter, who urged him to “sacrifice much or all for the public good” when needed (Rowbotham 14). Carpenter’s essay, The Simplification of Life, was published in July of 1896, in volume 3 of The Savoy. In it, Carpenter employs rhetorical strategies to advocate for a reevaluation of the materialist norms prevalent in late nineteenth-century England. He does this through the strategic use of terminology from various fields to unite the very divided society of the Victorian Era.

Dramatic or “Dramatism”?

Kenneth Burke is a contemporary theorist who introduced the concept of “Dramatism” to analyze human interactions via language, asserting that individuals are “driven to act in reaction to specific circumstances” (Burke 45). From this framework, he devised the “Pentad” to scrutinize human motivation, comprising act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose (Hochmuth 142). Each element of the pentad serves as a pathway to uncover the underlying motivations behind linguistic expressions (142). These pentads are combined in pairs to dissect rhetorical tactics, revealing how speakers or authors execute their motivations through precise language selection. In The Simplification of Life, Carpenter applies the “act-agent ratio” (Rountree 355), contending that materialistic actions perpetuate a cycle of accumulation, resulting in individuals becoming “muddle-headed” (Carpenter 95). Burke’s rhetorical analyses consistently underscore the significance of terminology in shaping one’s understanding of reality. He suggests that selecting the apt term from a multitude of options signifies the existence of varied interpretations of the same reality (Burke 45). This concept is pivotal in examining Carpenter’s work within the backdrop of divergent ideologies and visions for British society. Carpenter strategically employs specific language of many different understandings of reality, to steer readers towards his own interpretation, endeavouring to persuade them to embrace his critical views on the materialistic and capitalistic practices of the Victorian bourgeoisie.

The Immorality of Simplicity

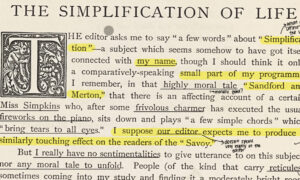

In the essay’s opening sentence, Carpenter promptly distinguishes himself from the editor, claiming that he was requested by him, to speak on ‘Simplification’ (Carpenter, 94). This initial assertion not only grabs the reader’s attention by suggesting Carpenter’s credibility through his close association with the editor, who specifically sought his input for the Savoy, but also separates Carpenter from the editor, who is linked with materialism, corporate interests, and the bourgeoisie. The significance of this differentiation is emphasized by Carpenter’s mention of the “highly moral tale of ‘Sanford and Merton’” (94). This implies that the editor likely expected a similar sentimental narrative focused on morality, but Carpenter declares his intention not to conform to this expectation. Once again, this distinction between his own intentions for his work and those of the editor suggests multiple ideas. Firstly, it indicates Carpenter’s divergence from traditional moral narratives, signalling his rebellion against the established order. Secondly, this emphasis on Carpenter’s independent thought and resistance to conformity adds weight to his theories by presenting them as grounded in empirical evidence and “the science of life” (94) rather than mere moral assertions. This positioning implies that Carpenter perceives morality—what is considered right or wrong—as subjective rather than an objective truth, and that the moral standards upheld by the upper echelons of nineteenth-century England are not necessarily correct. Throughout his introduction, Carpenter hints at a disdain for individuals who adhere blindly to societal norms of morality without considering what truly brings fulfillment in their lives. By rejecting the idea of blindly following conventional morality, Carpenter advocates for a deeper examination of one’s actions and values, underscoring the importance of authenticity and personal fulfillment over superficial adherence to societal expectations.

Christian Socialism V. Decadence

Edward Carpenter’s astute utilization of biblical language in The Simplification of Life serves as a strategic maneuver to advocate for Christian socialism within the context of the burgeoning decadent movement of late nineteenth-century Europe. Carpenter strategically incorporates biblical language not merely as a stylistic choice but as a deliberate tool to promote Christian socialism amidst the emergence of the decadent movement in late nineteenth-century Europe. His utilization of religious language serves dual purposes: firstly, to align his socialist ideals with a moral and ethical framework familiar to his contemporary audience; and secondly, to cast a critical gaze upon the prevailing societal norms and values of bourgeois society. It is essential to acknowledge Carpenter’s endeavour to resonate with the diverse ideological stances within Victorian society. While he critiques conventional morality often presented in English literature, the biblical language subtly connects to morality in a more nuanced manner. In his article “Christian Socialism as a Political Ideology,” Anthony Williams explores how Christian socialists strategically employ biblical language in literature to challenge capitalism and materialism in a non-confrontational manner (Williams 3). Through the use of biblical language, Carpenter bridges the divides between the decadent movement, radical socialism, and traditional Christian morality, offering a nuanced critique of late nineteenth-century bourgeois society. By skillfully weaving biblical language into his discourse, Carpenter not only aligns his socialist ideals with familiar moral frameworks but also navigates the complex landscape of late Victorian ideologies, thereby presenting a nuanced critique of bourgeois society.

Carpenter and Ideology

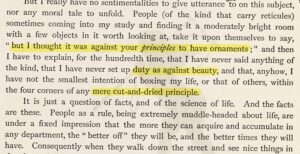

Edward Carpenter employs strategic rhetorical techniques at the outset of his argument for leading a simple life, laying the groundwork for his later advocacy by challenging prevailing ideologies and emphasizing the importance of individual exploration. To effectively sway readers toward his subsequent arguments advocating for simplicity in life, Carpenter initiates by highlighting the constrictive nature of ideology, prompting readers to scrutinize their existing “principles” (Carpenter 94). He subtly achieves this by addressing a common assertion he encounters—that “it was against [his] principles to have ornaments” (94). In response, Carpenter rebuffs the notion of pitting “duty against beauty” and rejects confining his life to “mere cut-and-dried principle” (94). His inclusion of the binary opposition of duty versus beauty is particularly noteworthy within the contemporary context, where movements such as avant-gardism, aestheticism, and decadence were burgeoning. The reliance on binaries proves inherently limiting, framing issues in stark contrasts rather than acknowledging a spectrum of possibilities. Moreover, the notion of “cut-and-dried principle” (94) reinforces the imagery of constraint while also exemplifying the straightforward language mirroring Carpenter’s concept of simplification. This emphasis on constraint lays the foundation for Carpenter’s subsequent advocacy of individualism, wherein he contends that simplification manifests in diverse forms for each individual. Furthermore, his use of straightforward language fosters a conversational tone in the essay, mitigating any perceived power imbalance between the author and readers. By challenging prevailing ideologies and emphasizing individual exploration, Carpenter sets the stage for his later advocacy of simplicity, demonstrating a strategic approach to engage readers and lay the groundwork for his argument.”

Scientifically Speaking…

Edward Carpenter strategically employs scientific language to lend credibility to his philosophy of simplification, leveraging terms typically associated with scientific inquiry to imbue his work with objectivity. Carpenter utilizes scientific terminology not to present his work as scientifically researched, but to infuse his philosophy with the perceived objectivity of scientific endeavors. For instance, he asserts that his work concerns “facts, and the science of life” (Carpenter 94), strategically repeating terms like “facts” and “science” (94, 95) to align his argument with the credibility often attributed to scientific inquiry. A similar strategy is evident when he equates possessions with responsibilities and “the diseases connected with them” (95), illustrating how accumulating possessions leads to increased responsibilities and perpetuates a cycle of dissatisfaction. Later, Carpenter employs the metaphor of “surgical operation” (95) to explain the removal of fixed ideas, lending alleged scientific credibility to his earlier critique of ideology. This choice of terminology not only suggests the deeply ingrained nature of materialism in the Victorian Era but also aims to persuade readers through subtle implication, according to Burke’s concept of terministic screens. Through his strategic use of scientific language, Carpenter not only enhances the credibility of his argument but also employs subtle persuasion techniques to engage readers and advance his philosophy of simplification.

The Irony of it All

The publication of Carpenter’s essay in the Savoy, a periodical affiliated with the decadent movement and renowned for its provocative content, adds complexity to his message. While The Savoy was less commercially driven compared to other little magazines like The Yellow Book, Carpenter’s critiques targeted accumulation and materialism (Keep). This juxtaposition between Carpenter’s message and his publications not only illustrates his innovative approach to social reform but also underscores the inherent tensions between mainstream Victorian values and the emerging Christian Socialist movement. Carpenter’s essay sheds light on the implications of publishing in The Savoy, particularly regarding its criticism of materialistic bourgeois values, given its emphasis on “the simple life” and biblical analogies. This contrast prompts reflection on whether Carpenter’s rhetorical strategies align with ethical standards. Hochmuth asserts the ethicality of rhetoric is intertwined with persuasion, which is inherent to language and communication. Herrick, in his text “An Overview of Rhetoric” suggests that the ethicality of persuasion hinges on whether it’s deceptive or manipulative. Carpenter’s strategies, while astute, don’t necessarily cross into deception. Instead, readers interpret his text through their own lenses, possessing the ability to critically analyze it for merit. If Carpenter’s intention is to broaden bourgeois perspectives beyond conventional habits, then his use of rhetoric can be deemed ethical.

Conclusion

Edward Carpenter emerges as a figure of significant complexity and influence whose impact extends beyond his own time. Despite his privileged background, he broke societal conventions to champion causes such as social justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and advocating for a simpler lifestyle. Through his adept use of language and rhetorical techniques, examined through Kenneth Burke’s framework, Carpenter maneuvered through the intricate social fabric of late Victorian society. His essay, The Simplification of Life, not only challenges prevailing norms but also lays the groundwork for a deeper examination of individual values and societal expectations. Carpenter’s enduring legacy highlights the enduring power of language and the timeless relevance of his ideas in contemporary discourse.

Works Cited

- Anthony A.J. Williams. Christian Socialism As Political Ideology : The Formation of the British Christian Left, 1877-1945. Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. EBSCOhost, https:// search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2600747&site=ehost-live.

- Burke, Kenneth. “Chapter Three — terministic screens.” Language as Symbolic Action, 31 Dec.1966, pp. 44–62, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520340664-005.

- Carpenter, Edward. “The Simplification of Life.” The Savoy vol. 3, July 1896, pp. 94-97. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020.

- Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv3-carpenter-simplification/

- Day, Thomas, et al. The History of Sandford and Merton. Broadview Press, 2010. https:// torontomu.summon.serialssolutions.com/search

- Ganeri, Jonardon. “Cosmic consciousness.” The Monist, vol. 105, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2022, pp. 43–57, https://doi.org/10.1093/monist/onab022.

Herrick, James A. “An Overview of Rhetoric.” The History and Theory of Rhetoric: An Introduction, Routledge, New York, NY, 2018. - Hochmuth, Marie. “Kenneth Burke and the ‘New rhetoric.’” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 38, no. 2, Apr. 1952, pp. 133–144, https://doi.org/10.1080/00335635209381754.

- Keep, Christopher. “General Introduction to The Savoy (1896)” Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/savoy-general-introduction/

- King, Frederick D. “The Decadent Archive and the Long History of New Media.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 49, no. 4, 2016, pp. 643–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26166581.

- Rountree, Clarke, and John Rountree. “Burke’s Pentad as a guide for symbol-using citizens. Studies in Philosophy and Education, vol. 34, no. 4, 23 Aug. 2014, pp. 349–362, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-014-9436-1.

- Rowbotham, Sheila. Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love. Verso, 2009.

- Tsuzuki, Chushichi. “Carpenter, Edward (1844–1929).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 6 Feb. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.013.32300.

Note: Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.