19th Century Paganism and Female Liberation—An Exploration of William Sharp’s “The Black Madonna” (1892)

Imagine you are a woman in 19th century Britain bound by the puritan ideals of the Christian church, where do you turn to find independence or autonomy? Well William Sharp beckons us to explore an unconventional avenue of female empowerment—that occasionally, female empowerment may call for a touch of paganism. “The Black Madonna” published in Sharp’s single issue release of The Pagan Review (August 1892), exemplifies the intersection of neo-paganism and feminism. Sharp centers his story on a powerful female deity whose agency is threatened by a chief priest, through an implied sexual assault. The story ultimately ends with the goddess reclaiming her power and punishing the man.

Interestingly, Sharp’s narrative disrupts the patriarchal doctrines of the Christian church (particularly that of gender hierarchy and sexuality) that had practically governed the social norms of the Victorian era (Collette 174). This, in tandem with the Pagan theme of the magazine, leads me to believe the story to be a greater reflection of how late-Victorian esoteric spirituality allowed for female liberation. It is a nuanced expression of the ways in which Victorian women navigated their religious and existential landscapes, to carve out spaces of autonomy and resistance within a male-dominated religious ethos. Through a 19th century neo-pagan and feminist lens, this exhibition seeks to explore William Sharp’s “The Black Madonna” and how it represents the underrepresented feminist spaces of late-Victorian Pagan groups.

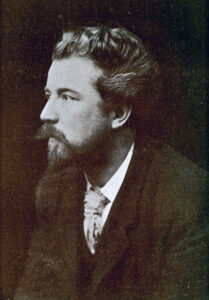

WILLIAM SHARP

Dennis Denisoff, co-editor of Yellow Nineties Online, documents the life of William Sharp in William Sharp [pseud. Fiona Macleod, W.H. Brooks] (1855-1905)”. Sharp was born in Scotland in 1855, and from childhood was inspired by Gaelic singing and storytelling, instilling within him a fondness for mysticism. Sharp fostered his affinity for nature/spirituality by studying philosophy, occultism, spiritualism, folklore and poetry at Glasgow University at the age of 18 (Denisoff). In the 1890s Sharp joined the Hermetic Order of The Golden Dawn, and became a central figure in the Celtic Twilight or Celtic Revival. In 1892 Sharp published The Pagan Review, of all his literary works this became the most infamous. Denisoff addresses the many pseudonyms of Sharp, the most notable being that of Fiona Macleod. He notes that Sharp kept the identity hidden well up until his death, but was condemned for his feminine voice. He also suggests the pseudonym was also representative of Sharp’s own conflicted feelings of his own gender identity, where he felt at times felt more like a woman than a man. His gender identity may have also heavily influenced his avocation for women, and an inclination towards Paganism; wherein The Golden Dawn lacked gender based hierarchies nor definite gender roles, allowing for fluid/loose binaries of gender (Pecasting, 4)

The Pagan Review

The Pagan Review was a magazine published by William Sharp in 1892, and ceased publication after only a single issue. It was riddled with Decadence and superficial understanding of earth-based spiritualities. The Pagan Review more so captures Sharp’s aforementioned love of nature-based spirituality. In the foreword of his magazine, Sharp makes his intentions very clear. He strives to capture a “new paganism” that incorporates both old and new paganism to better serve the people of his present day. He also is quite feminist in his pursuit to create an inclusive religious space, stating “first, the rubbish must be cleared away… women no longer have to look upon men as usurpers, men lo longer to regard women as spiritual foreigners” (Sharp 2). Despite the feminist subtext he did not want to have the magazine overly read into, as Sharp created the magazine simply for “literary purposes”, or art for solely art’s sake.

“THE BLACK MADONNA”

The magazine begins with the story of “The Black Madonna” of which is its longest contribution. It opens with a vivid description of a ritual performed at sunset for The Black Madonna, a powerful female deity represented by a black marble statue (Sharp 5). Outside of the story The Black Madonna is a prominent female religious figure that spans centuries, beginning as the Egyptian goddess Isis, to that of Mother Mary (Foster 4). This religious syncretism is integral to the text as the identity of the Black Madonna is never pinpointed to a single figure. Instead, Sharp blends the meanings using words like “Nubian” and also calling her “Mother of Christ” (5–6). In the story, the Priests who worship her repeatedly deem her as “Mother of God” , “Slayer”, and “Saver” (14–17). Thus, exaggerating her godly qualities, she is a woman who creates, saves and also destroys. The priests then sacrifice five virginal maidens in her honor. However, Sharp labels them “The Victims”, allowing them innocence and implies 5 women caught up in a power struggle with the church, while still granting power to The Black Madonna (7).

The height of the story lies in the relationship between Bihr, a chief and priest, and his lust for The Black Madonna. His obsession drives him mad, and forcefully assaults her. The scene is depicted as “And the man is wrought to madness by her beauty, and lusteth after her, and possesseth her with the passion of his eyes…the woman knows what he has done, he leaps to her and seizes her in his grasp, and kisses her upon the lips, and grips her with his hands till the veins sting in her arms. And all the sovereignty of her lonely godhood passeth from her like the dew before the hotbreath of the sun.” (Sharp 16-17). The “godhood” that is stripped from her could be read as her virginity, but I believe it to be more accurately read as her bodily autonomy. As Sharp positions her as “lonely”, in pain (“sting”), and most of all unconsenting (“possesseth”, “seizes”, “leaps”).

The narrative ends on the final day of the ritual where The Black Madonna goes up in flames, and Bihr is crucified by her. Sharp’s subversion of the cross is an explicit criticism of Christianity, paralleling the maidens before who are wrongfully killed for their womanhood and innocence, with The Black Madonna who punishes a man for his act of gender-based-sexual violence— the irony of a man crucified for impurity to that of Jesus who was crucified for purification, thus reasserting her power and reclaiming her agency.

THE HISTORY OF BLACK MADONNA

Beyond Sharp’s narrative of The Black Madonna, exists a religious figurehead that has endured across centuries“The Black Madonna is a powerful, visceral, and almost deviant archetype” (Foster 4), with the figure ever present in a variety of disciplines including art history and religious studies. Its meaning is largely based on its geo-political context, often presented as a Marian figure in the West and in early Latin America (Foster 5). The Black Madonna is an example of the influence of African religions on other religious ideologies, yet the combination of gender and race in a powerful deity is absent in patriarchal religions like Catholicism (Michello 1). The Black Madonna connotes a dark and powerful woman, contrasting the image of Mother Mary, fair and submissive (Michello 2). Outside of monotheistic-Abrahamic religions, this Mother-Goddess figure has also been adopted by other religious groups, such as the ancient cults of Isis (Foster 5)

Isis in the Victorian Era (The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn)

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the Pagan group Sharp belonged to, was a mystical and occult organization founded in London in 1888 by three Rosicrucian Masons late 19th century; known for its intricate system of ceremonial magic and esoteric teachings (Greer 1). Among the various deities and spiritual symbols incorporated into their rituals, the worship of the Egyptian Goddess Isis held significant prominence. In fact, their first temple was dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis (Greer 56; Pecasting 4). This dedication to Isis linked the Golden Dawn to Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophy (Pecasting 4). Her first esoteric essay, published in 1877, was entitled “Isis Unveiled”, and its success had turned the goddess into a central figure of the Victorian pagan revival (Pecasting 4). “Isis Unveiled” is a foundational text of the Theosophical movement and explores spiritual and occult phenomena, drawing on themes from Eastern and Western esoteric traditions (Blavatsky). Blavatsky’s “Isis Unveiled” delves into comparative religion, mysticism, and theosophy, presenting a synthesis of spiritual and philosophical ideas from around the world (1-635). Through religious syncretism Blavatsky does not simply portray Isis as an Egyption goddess, but rather a universal representation of ancient wisdom, mysticism, and the divine feminine principle.

Isis’s “new” (pertaining to 19th century esotericism) portrayal draws a similar parallel to the figure of The Black Madonna, with both figures lacking a single face but are instead representative of grander ideals of womanhood. Within The Golden Dawn, the syncretism of both religious inspirations and the roles of women, are apparent in one article written for the group by member Florence Farr; a popular Victorian actress and high priestess (Greer 119; Pecasting 4). She states “‘I am the mighty Mother Isis; most powerful of all the world…Christ is the Heart of Love, the heart of the Great Mother Isis…She is the Holy Grail.’” (Greer 119). The diction highly resembles that of the descriptors Sharp uses in “The Black Madonna”. Especially, that of “Mother of Christ” and “Nubian” which suggests Isis, thus it is evident that his character is largely informed by his own Pagan religion. This is important as it adds greater context to her godly capabilities, she is not simply a fictional character but one who has real power, worship, and influence in the real lives of Victorian people.

MYSTICISM AND FEMALE LIBERATION

Unfortunately Late-Victorian feminism has often been dismissed due to its lack of organized collective action, deemed as acting as a web of groups without consensus (Elford 32). However author Jana Elford contends that by “not adhering to a single or monolithic feminist agenda, these women were involved in various and multiple overlapping social clubs and organization” (33). Thus feminism in the 19th century blended and created an intersectional look at womanhood, which Elford notes extended into their spiritual beliefs and “religion-based associations”. A sentiment furthered by Carolyn Collette who argued that much of late-Victorian suffragists based themselves around religion. She argued that many of them channeled their spirituality into their fight, “When they invoked religion, they did not mean the forms of liturgy or the doctrines of churches; they meant the spirit of divinity that mystics sought” (Collette 173). When much of female oppression is rooted in the patriarchy of the Christian church, it only makes sense that women sought out other spiritual networks (Collette 174). Within The Golden Dawn the very thing happened with Florence Farr, who was a suffragist herself (Pecasting 4). Farr was heavily influenced by her pagan faith, she advocated for feminism, and for women to use their transformative nature to break free from Victorian norms (Pecasting 4).

IMPORTANCE

Sharp’s reinterpretation of The Black Madonna is likely based on capturing the essence of powerful female figures, modeling his character off of The Golden Dawn’s image of Isis. It is also a representation of how late-Victorian women are beginning to be granted greater freedom and power through their spirituality. Most importantly, the power Sharp affords the female characters, works directly with the rejection of the church as they reclaim their autonomy from their wrongful religious convictions and acts of gender based violence. It is unfortunate there is very little published on the magazine, let alone on “The Black Madonna”. In the one journal article that does make mention of it, author Bennedicte Coste poses it as a cautionary tale of sexuality and desire, as opposed to the destruction caused by sexual assault (6-7). And despite being titled “Late Victorian Paganism…” Coste makes no mention of any established 19th century pagan groups. However, looking at Sharp’s own pagan group, we are able to see how Victorian women were represented in non-judeo/christian religious spaces. The Black Madonna is a relic and beyond its time in affording women justice and literal Female empowerment.

Works Cited

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. Isis Unveiled: Theology. J.W. Bouton, 1891.

Collette, Carolyn P. “Hidden in Plain Sight: Religion and Medievalism in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement.” Religion & Literature, vol. 44, no. 3, 2012, pp. 169–75.

Coste, Bénedicte. “Late-Victorian Paganism: The Case of the Pagan Review.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens (Online), no. 80, 2014, pp. 2-12. ProQuest,

Denissof, Dennis. Sharp_bio – Yellow Nineties 2.0. https://1890s.ca/sharp_bio/. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

Elford, Jana Smith. The Late-Victorian Feminist Community on JSTOR. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/stable/24877740. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

Foster, Elisa A. “Out of Egypt: Inventing the Black Madonna of Le Puy in Image and Text.” Studies in Iconography, vol. 37, 2016, pp. 1–30.

Greer, Mary Katherine. Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses. Park Streeet Pr, 1995.

Michello, Janet. “The Black Madonna: A Theoretical Framework for the African Origins of Other World Religious Beliefs.” Religions, vol. 11, no. 10, 10, Oct. 2020, p. 511. www.mdpi.com, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100511.

Pécastaing-Boissière, Muriel. “‘Wisdom Is a Gift given to the Wise’: Florence Farr (1860-1917): New Woman, Actress and Pagan Priestess.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens (Online), no. 80, Autumn 2014, pp. 2–10.

Sharp, William. The Pagan Review. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/ThePaganReview. Accessed 21 Apr. 2024.