The Narcissus’s Path to Social Independence – A Critical Exploration of Dorothy Herbertson’s “Spring in Languedoc” (1895)

Dorothy Herbertson

Dorothy Herbertson (originally known as Fanny Louisa Dorothy Richardson) was born in 1864, birthplace is unknown. Herbertson was known as an author and teacher. Within the year of 1893, Dorothy married her husband Andrew John Herbertson, an author, editor, lecturer and a direct contributor to The Evergreen magazine alongside Dorothy. Both Dorothy and Andrew Herbertson were mentored under Patrick Geddes, the founder and main editor of The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal. Dorothy Herbertson’s written work “Spring in Languedoc”, categorized under “Spring in the World” was the only written piece by a female author in Evergreen’s first volume, making her the first female author published in the Evergreen Magazines. Dorothy showed interest in work that delved into aspects of socioecomics. An example of this is shown when Herbertson “wrote the English bibliography Le Play, probably between 1897” (Gilbert, 1965) alongside “Spring in Languedoc” which was published a few years prior in The Evergreen’s Volume 1, “Spring” in 1895. The bibliographical paper describes French sociologist Leplay, and his theories surrounding the belief of family structure as an essential element of society. These methodologies explored and how economic, social, and cultural factors affect family structure. Dorothy would pass away in the year 1915 in Spriggs Holly, Radnage, Buckinghamshire, England.

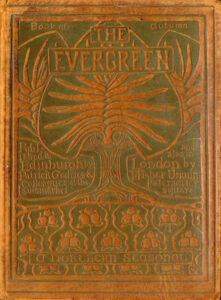

The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal

The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal is a magazine series published within May of 1895 by Author, Professor and Scientist Patrick Gedder. The magazine was published semi-annually from 1895 to 1896. The series consisted of 4 volumes: Spring, 1895, Autumn 1895, Summer, 1895 and Winter, 1896-97. The Magazine’s main objective was to express “a message of social regeneration by uniting art and science in the architecture of the page” (Kooistra, 2016). The Magazine’s focuses on the beauty, culture, and lifestyle of the Northern regions, From Pan-Celticism, Scottish Renaissance with a focus on nature, sustainability, as well as the changing seasons.There are also international inspirations that are encorporated through the Evergreen series. Patrick Geddes saw The Evergreen magazine “as a resource for—and perhaps even a manifesto of—cultural evolution” (“Patrick Geddes”). The Evergreen Magazine is not only a source of Celtic-inspired literature, The Evergreen is an “expression of a larger socio-political vision” (Kooistra, 2016).

“Spring In Languedoc” – Through A Critical Lens

The creative essay “Spring in Languedoc” by Dorothy Herbertson was published within The Evergreen‘s Volume 1, “Spring” magazine in 1895. Herbertson’s poem vividly describes how beauty within landscapes comes naturally in a place like Languedoc. The essay’s first line characterizes the typical signs of spring in their bordering provinces when “the sun returns, the flowers reappear, the hedgerows and trees clothe themselves in green, and the time of the singing of birds is come (line 2 & 4). Compared to their neighbouring southern provinces, Languedoc’s “cypress and pine and olive have never shed their leaves, the sun has shone even when the icy mistral blew from the frozen gorges of the snow-clad Cevennes, and there has been no day on which we could not pull a handful of flowers” (line 5 & 9) This is to show the Languedoc’s beauty as timeless. Although Herbertson’s essay describes the winsomeness of Languedoc’s spring season, the essay also displays aspects of decay within the season: “Maguelone, greatly fallen, its good days done. No sign of Spring there save for the violet wall-flowers clinging among the grey stones. Life has ebbed away from it, and left it lonely with the great dead who sleep in its forsaken aisle” (line 34 & 38) This part of the essay is meant to express that no matter the beauty and resilience one has, death and end are something inevitable. Herbertson concludes the essay on a note of optimism “Nevertheless we shall not die but live. A new spirit is abroad in the world, and around us the whole land is breaking into song” (Line 45 & 47) along with “There is no hint of weariness, or disillusion or distrust in this new singing-time. This land is dear to the sun, and it is good to be alive therein. It is the land of fig and vine and olive, of love and wine and song” (line 64 & 68). The essay is meant to express that, despite death being something of certainty, that does not mean it is an end. Optimism for change is what leads to a greater transformation.

The Significance of Narcissus

Herbertson often refers to the Greek mythological tale of Narcissus as a focal point within “Spring in Languedoc”. The tale begins with Narcissus, the son of Cephiuss, the river god of Greece, and Liriope, a nympth. Narcissus was known as a beauty amoured by all. Although Narcissus possessed great beauty, he also found himself fanatical about his appearance. This gave Narcissus a personality of arrogance and vanity, where he could not love anyone who did not possess beauty as grand as his. While Narcissus walked within the forest, he discovered his own reflection in the river, “died, and was turned into the flower of like name” (Spawford, et al, 2016)

Herbertson utilizes the Greek tale to depict the vibrancy of Languedoc’s spring season: “The narcissus is out at Lattes. How wonderful to find oneself in the long low meadows among the, the tall, sweetscented blossoms which are scattered as thickly as daisies on an English sward! They edge the little watercourses, nestling round the roots of the stunted willows” (line 23 & 27) Narcissus represents the yellow daffodils described in the passage as being scattered across the river streams in southern france. Narcissus’s universal beauty, from his transformation into a yellow daffodil, alludes to Languedoc’s picturesque spring landscape. Herbertson also uses Narcissus in a solemn manner to depict loss within spring and Languedoc, “Even here among the sunny meadows, steeped though we be in the sensuous joy of the moment, interpreted to us by the heavy scent of the narcissus, comes a cry from the Everlasting Past, a rustle of the Wind of Death” (line 42 & 43) The lingering scent of the narcissus flower portrayes a marking of loss. Similarly to the Greek Tale, where narcissus

The essay’s 17th line “The yellow flowers come first, then the white and blue” (line 17 & 18) Foreshadows the innate significance of what spring & The essay’s symbolism is transformation through beauty and death.

Yellow is often used to represent joy and hopefulness and is often associated with the spring and summer seasons. Yellow also represents the Narcissus, as he is both a yellow daffodil and a man praised for his universal beauty. White traditionally is symbolized with purity and cleanliness, but it can also represent coldness and isolation— a representation of isolated warmth that passes as the season transitions to the winter season. The colour blue can represent gloom, but it can also symbolize intuition, freedom, and imagination. This serves as a representation of spring, the season of transformation.

The narcissus is a representation of all three attributes. He begins as an iridescent beauty, this represents Languedoc’s beauty and the summer season. When Narcissus dies from drowning in the river, this represents the winter season overtaking the beauty that lies within summer, and when Narcissus turns into a daffodil, this represents spring and the transformation that comes with death and winter.

Herbertson uses the story of Narcissus as a portrayal of beauty, death, and rebirth in the former province of Languedoc.

Languedoc’s History

Languedoc-Roussillon, better known as Languedoc, is located on the southern coastal line of France. Languedoc was previously recognized as a province before the uproar of The French Revolution (1789-1799). Commoners began to grow aggrieved with the Crown for overtaxing, resulting in commoners “paying more in the name of fiscal equality” (Sutherland, 2006), The Protestan Catholic Church Relations, where the Crown poorly attempted “regulate church‐state relations”. This caused many riots and uproars, as well as formations of political clubs, including the Jacobins, said to be one of the most influential political organizations. Through their attempt “to solidify a democratic republic, the Jacobins tried to silence provincial voices during the Terror” of the revolution. This resulted in the voices of provinces being discarded during the uproar and the Crown proposing “changes in the fiscal system and with provincials…in the name of ancestral rights and charters” (Sutherland, 2006). This resulted in abolishing provinces and referring to them as départements’, including Languedoc. Languedoc was known as an agricultural province where “the conditions, needs, and produce of the soil strongly influenced political attitudes and social position” (Loubère, 1968). Languedoc is made up of the “departments of Gard, Hérault, and Aude” (Loubère, 1968). The province was divided by mountains and rivers, which separated Upper and Lower Languedoc. On the lower plain’s of the départements, where population is scarce, they transform into large vineyards. This introduced Languedoc to “capitalist agriculture techniques” (Loubère, 1968) where they would make wine, cereal, and silk produce. Although Languedoc adapted capitalistic agriculture techniques into their vineyard sourcing, they took a rather sustainable approach to their production. Since the vineyards “represented a vast amount of labor carried on generations of landowning peasent families” (Loubère, 1968) Because land in southern france was “more divided, the peasantry often owned their land”(Loubère, 1968) and “much of their food, therefore, was for self consumption” (Loubère, 1968). The rise of vineyards not only positively impacted Languedoc’s economy but it also had a fair impact on Languedoc’s social structure. From the rise of vineyards also came the increase of the labourers, to the point where they were “outnumbering the owners in some communes by four to one” (Loubère, 1968). This bridged the gap between elitists and commoners due to the laborers, who are considered lower class actively growing Languedoc’s economy while still having the sustainability of owned land and endless resource to luxuries such as wine and silk as well as natural food resources like cereal grains. All these assets would only typically be accessible to the elitists of society with bountiful financial funds. This led to Languedoc being associated as a province of cultural innovation with “inventive patterns of work and sociability” (Miller, 2021) which fosters the “adoption of new methods, ideas, and products” (Miller, 2021). It was through Languedoc’s new and improved social progress that it transformed “all levels of society for political and economic dialogue, which paved the way for them to participate in public affairs and improve their material circumstances” (Miller, 2021) Languedoc’s transformation of work social sustaniability lead the province to a maximization of growth in beauty, economics, and innovation despite their loss of provincehood after The French Revolution.

“Spring In Languedoc” – The Bigger Picture

Upon first impression, “Spring in Languedoc” reads as dedicatory literature to the allure and beauty of southern france by describing it’s landscape as a place where “air is

fragrant, the sky is cloudless, and the sunshine and the Spring day stir the blood like wine” (line 29 & 30) due to Languedoc’s innate beauty, which never falters. While this is true, that is only a mere fraction of the essay’s significance. Through careful analysis of Dorothy Herbertson’s creative essay, “Spring in Languedoc” was published to highlight the importance of advocacy for cultural and political independence. The symbolic message behind spring being a transformative period after death in “Spring in Languedoc”, serves as a reflection of the province’s historical loss that led to Languedoc’s rich, innovative landscape and culture, which it is now known for. Both The Evergreen and Dorothy Herbertson’s works aspire to promote the ideation of social regeneration. Herbertson’s written bibliography, “Leplay and Social Science” (Herbertson, 1897) looks into socioeconomics affect family structure. Socioeconomics delves into how an economic state affects and forms social processes and progress. When looking at Languedoc’s rich history, which Herbertson bases her creative essay upon, their economy and landscape flourishes due to the breaking of classist social stereotypes, and their innovative work habits of producing both natural and luxury resources for sustainability rather than overconsumption.

Narcissus, in this instance, can also symbolize the harm of finding aestheticism in decadence, a movement heavily incorporated within the 19th century. Similar to Narcissus, decadence is self absorbed in the idea of beauty to the point where it leads to decline. This may resemble the over-comsumption of luxury goods, capitalistic idealism, where lavishment in objects must be mass produced at the expense of lower-class people. In the case of Narcissus, where his beauty is beyond compare, it is his vanity and self-obsession with his beauty that ultimately lead to his death. Herbertson utilization of Narcissus in a tale of Spring is meant to tell readers that although 19th-century society is built off of the decline of obssessing over luxury (this can also represent the season of winter, a time of loss and isolation), there is still room for transformation if society does not define them, similarly to Languedoc’s evolution after the province’s loss from the French Revolution.

Importance

In conclusion, Dorothy Herbertson’s creative essay “Spring in Languedoc” is meant to show readers that the vitality in effective societal and economic evolution relies on society abandoning the obsession of loss and materialistic beauty. Through innovative sustainability of resources. Once society learns to seek change within loss and decline, will then lead to an oasis of societal and economic evolution that benefits all aspects and individuals of society.

Works Cited

Spawford, Anthony, et. al. Narcissus(1) figure in greek mythology , 2016. Oxford Classical Dictionary. https://oxfordre.com/classics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-4334

Miller, Stephen. “Provincializing Global History: Money, Ideas, and Things in the Languedoc, 1680-1830. by James Livesey.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 22 Jan. 2021 https://academic.oup.com/fs/article/75/1/112/6118295?login=true

Loubère, Leo A. “The Emergence of the Extreme Left in Lower Languedoc, 1848-1851: Social and Economic Factors in Politics.” The American Historical Review, vol. 73, no. 4, 1968, pp. 1019–51. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1847387.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “GENERAL INTRODUCTION THE EVERGREEN: A NORTHERN SEASONAL (1895-1896/7).” Yellow Nineties 20, 2016, 1890s.ca/the-evergreen-general-introduction/.