Human Want and Need in a Religious Life

@ Copyright 2024 Jasmine Tsz Kan Tsang, Toronto Metropolitan University

Introduction

Religious symbolism has long been used in all varieties of media as a method to contrast the world and real human behaviour compared to the expectations set for humans. Charles de Sousey Ricketts and Charles Haslewood Shannon’s The Dial is composed of stories that use such religious symbolism to oppose society standards. The stories are written in the genres of fantasy, folklore and fairy tale with the intention of making the content more appealing to the general audience, and leaves interpretation as a choice to the reader.

“Open the Door, Posy!” by Laurence Housman tells the story of a mother and child in poverty situated in a town taken over by famine and fever. After their deaths, rather than being saved by the Lord and brought to salvation, they are visited by Death the Undertaker, Death the Taxman and Death the Sexton. The deal is for the daughter to buy a loaf of bread with the money that her mother has in order to bargain with Death on where the two of them are buried. But rather than rightfully purchasing the loaf of bread, the daughter steals it, and thus creates a string of troubles that this vice of theft has brought to them. At the end of the story, the mother scammed the 3 deaths by lying about having money in her clothes pockets, which she needs to return to the living to get.

The Authors

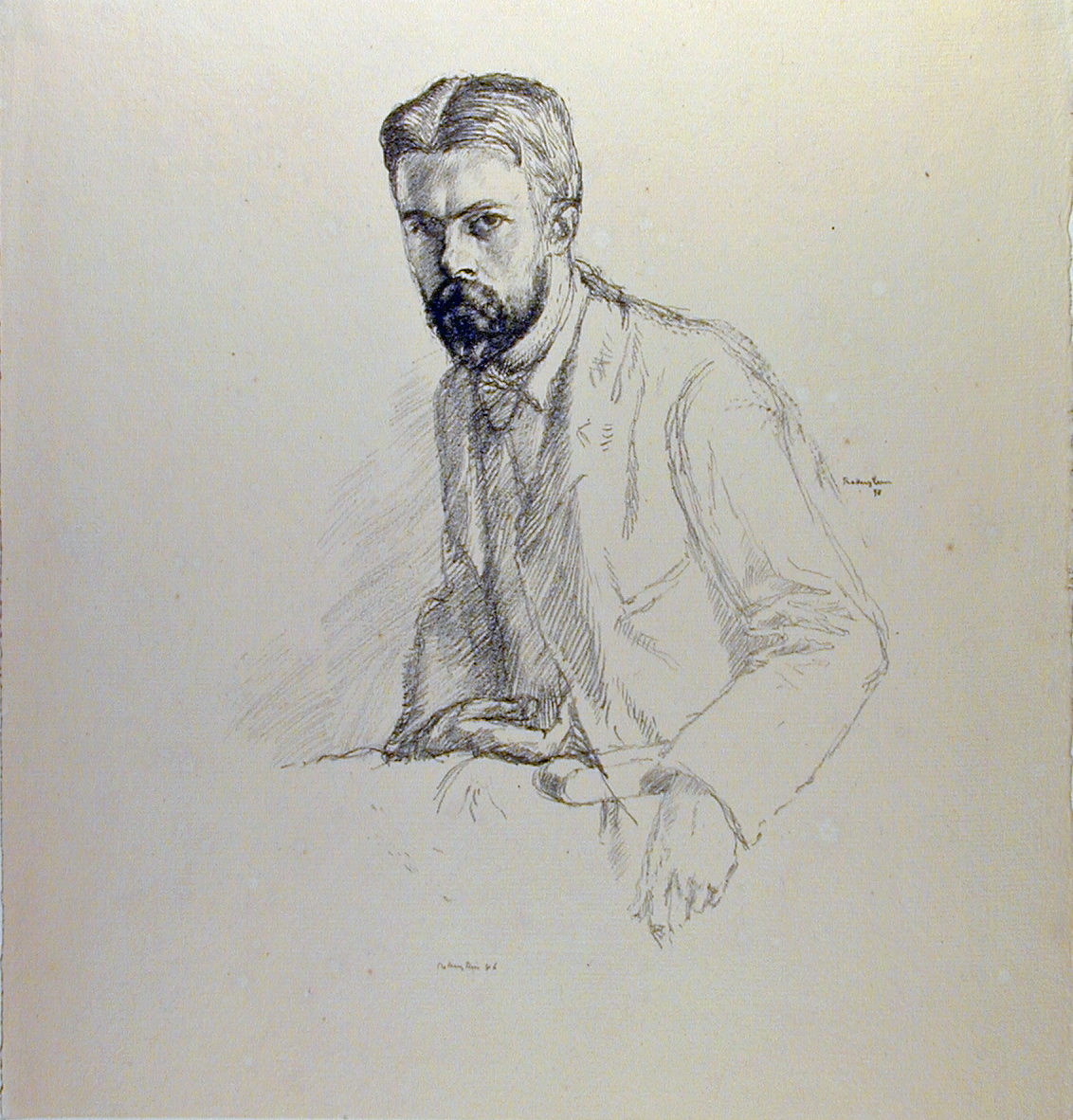

Charles de Sousy Ricketts and Charles Haslewood Shannon

Despite not being a believer of God in a Christian society, Ricketts often used Christian ideologies, incorporating them into his work to encourage discussion on the messages that ideas that his art seemed to tell and push. As Ricketts worked closely with Shannon, The Dial’s method of addressing religion and the social expectations set by those of a religious society can be sourced back to these two. Their intimate relationship consisting of two individuals of the same-sex would have been and still are being condemned by Catholicism as a sin. The stories within The Dial are well recognized as pieces that challenged the heavily christian society they live in, consisting of stories that are often led by characters that are placed in situations where it is less helpful to their livelihoods if they were to live a holy way of life.

The two of them met in art school and when Ricketts and Shannon’s work partnership officially began with the creation and publication of The Vale Press and then eventually The Dial magazine. When being interviewed by the public, Ricketts did not disclose much about his relationship with Shannon, but it is recorded that the two moved into a home together in 1866, one year before The Dial’s first publication. Outsiders would often ask about their relationship, but as their intimate relationship was not exposed much, questions about their relationship were gradually pushed away from sensitive details to focusing more on their art and its ideologies (Cook).

.

.

Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman was born in 1865 in rural Worcestershire and passed in 1959 in Somerset, being the sixth of seven children in a house that encouraged literary and artistic passions. His friendship with Ricketts’ began with their meeting in 1890 where Housman was encouraged to use more than just chalk in his illustrative works, moving in detailed pen work where he will work in copying and designing books, eventually designing one of his most recognized and innovative books, Goblin Market (1893). The recognition for this work eventually led to his illustrations being included in The Yellow Book, and then further collaborating with different artists to design other large project books.

Housman’s works in writing and illustration often reflected on social implications (Doussot). He lived his life advocating for the elimination of social prejudice with him having much bigger impacts in the twentieth century when it came to the advocation of women’s rights and a general advocate for the freedom of speech for sexual freedom. Many of his works were created in the style of fantasy, and when Housman’s eyesight slowly continued to decline, he turned to focus on writing where many of his poems, novels, short stories and plays were written in the style of fairy tales. In collaboration with Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, he contributes to the fifth volume of The Dial, “Open the Door, Posy,” a story about a mother and daughter who trick Death.

For his advocacy and work in book design, Housman was very well received by society. And so although he was not as popular as Ricketts or Oscar Wilde, Housman’s works are taken with serious admiration and consideration. It is also confirmed that he himself is a homosexual, and so his relationship with religion is similar to Ricketts’ and Shannon’s in that he creates works that encourage thoughts that go against the restricting expectations of Christianity.

Who Goes to Heaven

In the afterlife of the mother and daughter in “Open the Door, Posy!”, the two are visited by Death, and the story continues with them still struggling even after their deaths. The relevance of religion and Christianity here lies in the lack of God or a heaven for the mother and daughter to ascend to after their death. Rather than being graced by the Lord, they are visited by Death(s) who strike a deal as the two want to choose a better place for their coffins to be placed in. With the context taken from the author’s intentions in this era of rethinking society’s typical standards in the nineteenth century, it can be assumed that the mother and daughter are purposely excluded from being allowed into heaven. Just as the daughter committed the sin of theft by stealing bread as well as lying to her mom about how she attained the bread, it can be assumed that similar actions were committed when the two of them were still alive. In a situation where an entire community is stricken with “fever and famine”, it would not be surprising to think that selfish actions were done in order to keep the family safe and fed.

Human Want and Need in a Religious Life

As Ricketts and Shannon lived in a Christian church dominated society, their relationship was not always clearly defined to the public, but the two of them were often associated with LGBT figures. One of them was Oscar Wilde, a close friend to Ricketts whom was and still is a known homosexual that faced social injustice. Events such as these present the conflict of human want and need verses a religion that condemns these wants and needs.

It can be understood that oftentimes a religion such as Catholicism can be used to provide individuals with a sense of meaning and purpose which ultimately leads to fulfillment. By following these teachings, individuals are guided to let go of feelings of negativity or greed of fleeting wants. On paper, this idea sounds agreeable and may also be beneficial as the goal is human betterment. Where conflict may arise is how the Bible contains pieces of history that uphold traditional expectations for humans. The most relevant and general idea is that a man and woman are to be in a relationship that reproduces to cover and take care of the land that God provided. This originates from the story of Adam and Eve, and how they were essentially made for each other.

The relationship between humans and Catholicism requires individuals to navigate the tensions between immediate desires and deeper spiritual values. Ricketts’, Shannon’s and Housman’s works in literature and illustration argue for this point by highlighting the contradictions between humans and what God expects from them.

Conclusion

The Christian church dictates for humans to be devout followers of God. Outside of doing the typical routine of going to church, praying before meals, before sleep and anywhere and anytime outside of church because one is expected to always keep God in their thoughts, the Christian teachings also dictate that humans should live by the Bible and its virtues, and “Open the Door, Posy!” is a story that opposes these rules and expectations. This story along with the others in the publications of The Dial encourage the idea that as societies evolve and cultures shift, humans may also want to shift or in some cases like Posy and her mother’s, be pressured to shift from traditional ideologies presented by the Christian church on how to be a righteous person. Sacrifices must be made in order to survive as the world evolves and types of greed change, the Bible begins to become outdated in its ideologies.

It can be concluded that this story speaks on the very real struggles and burdens of the real world, and sometimes having hope in a religion is not enough to want to survive and live. Even the young daughter has the understanding that money is difficult to come by, and some actions must be made.

Works Cited

Cook, Matt. “Domestic Passions: Unpacking the Homes of Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 51, no. 3, 2012, pp. 618–40, www.jstor.org/stable/23265597. Accessed 5 Mar. 2024.

Doussot, Audrey. “Laurence Housman (1865–1959): Fairy Tale Teller, Illustrator and Aesthete.” Cahiers Victoriens et Édouardiens, no. 73 Printemps, Mar. 2011, pp. 131–46, https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.2190. Accessed 1 Mar. 2024.

Dowling, Linda C. “The Aesthetes and the Eighteenth Century.” Victorian Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, 1977, pp. 357–77, www.jstor.org/stable/3826709.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Laurence Housman (1865-1959),” Y90s Biographies, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/housman_bio/

Lieberman, Marcia R. “‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale.” College English, vol. 34, no. 3, Dec. 1972, pp. 383–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/375142.

Starzyk, Lawrence J. “‘That Promised Land’: Poetry and Religion in the Early Victorian Period.” Victorian Studies, vol. 16, no. 3, 1973, pp. 269–90, www.jstor.org/stable/3826035. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.